Mining the Physique Mystique with Homobilia's Barry Harrison

Whether nostalgic, a turn-on, or vessels for queer stories of the past, these images are priceless — and their future is anything but guaranteed

August 26, 2025

I recently read a news story whose hypothesis was that Millennials and Generation Z, in spite of an attraction to crypto gambling and online games of chance, simply are not inclined to gamble in the way we think of when we think of Las Vegas — you know, people parked at one-arm bandits or feverishly gathered around roulette tables.

The idea is that this, not just the economy, not just Trump’s tourism-killing tariffs, could be why Vegas is in a slump. Maybe it’s not a slump, but is instead a slow death.

It was jarring to me to think that, along with a shortage of cash, a systemic distaste for old-school gambling could be what is dooming Sin City. Such a tectonic shift is unsettling. But then again, Las Vegas has only been what we think of as Las Vegas for about 80 years, the blink of an eye in the grand scheme of things. Tastes change. After all, the main attraction in that city immediately prior to card games and all the stuff that happens — and stays — there was atomic tourism, which sounds like a blast but came and went with a bang.

I have often feared that another Atomic Era vice — ‘50s and ‘60s physique magazines — could also be a passing fancy.

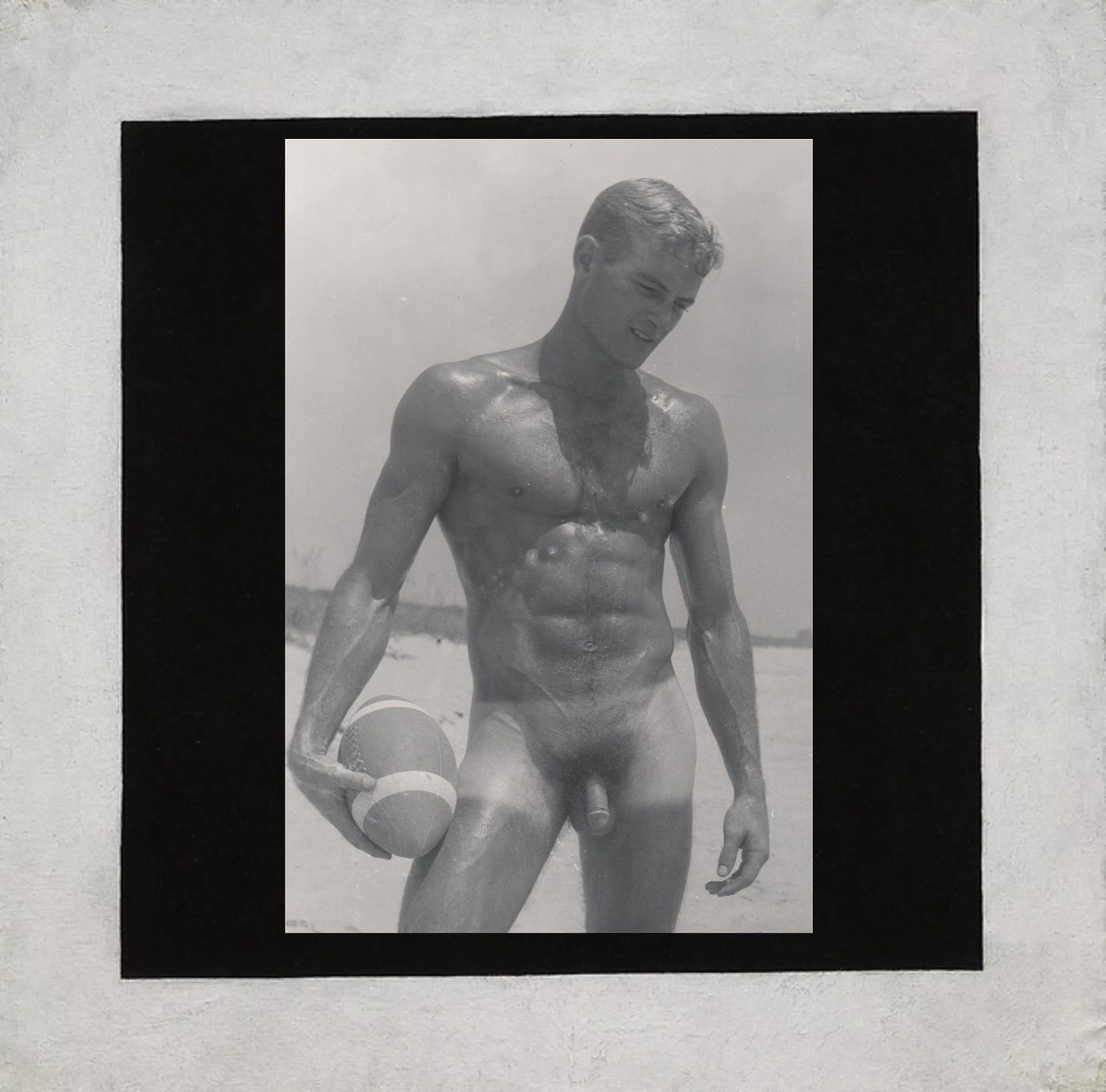

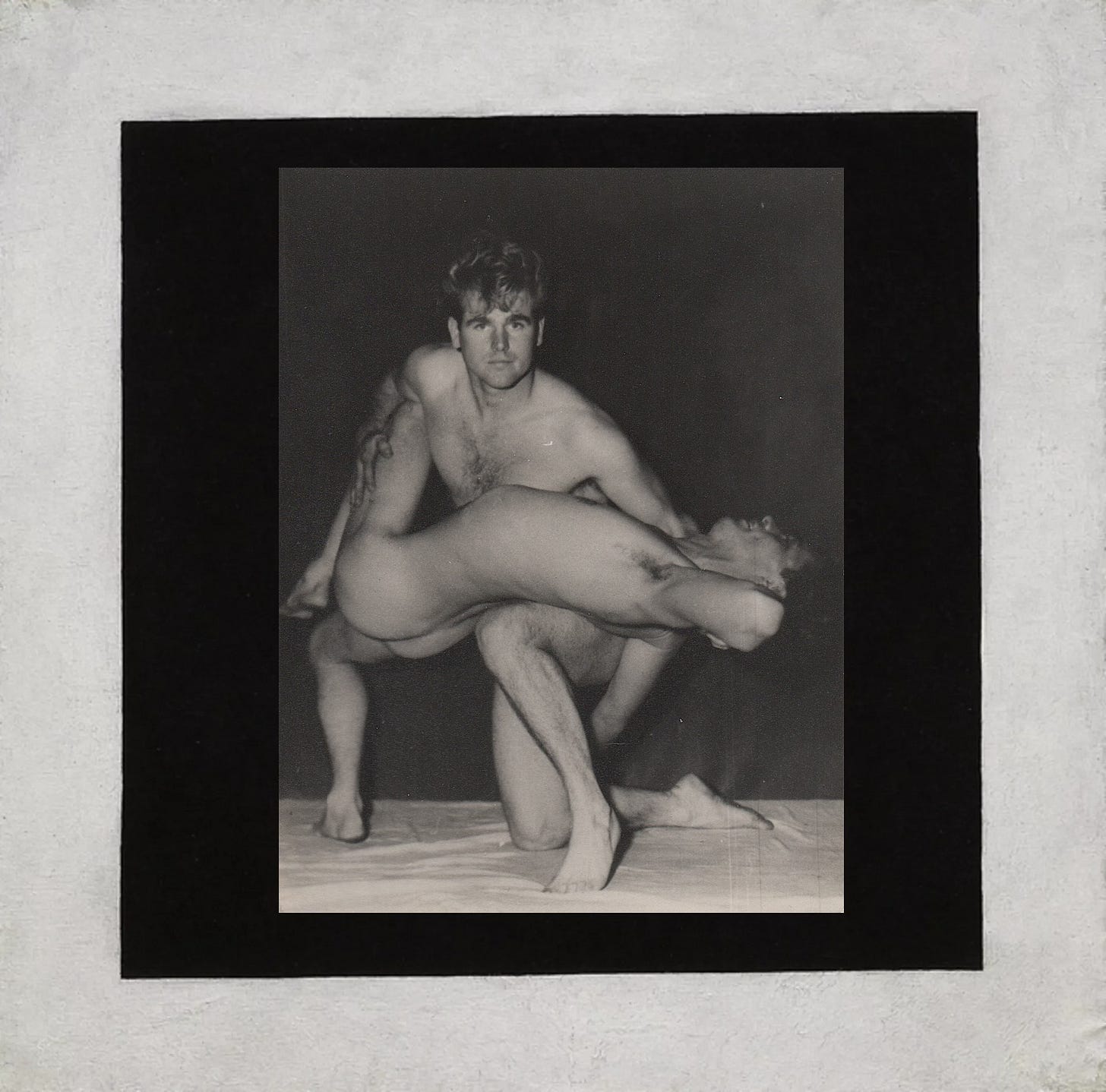

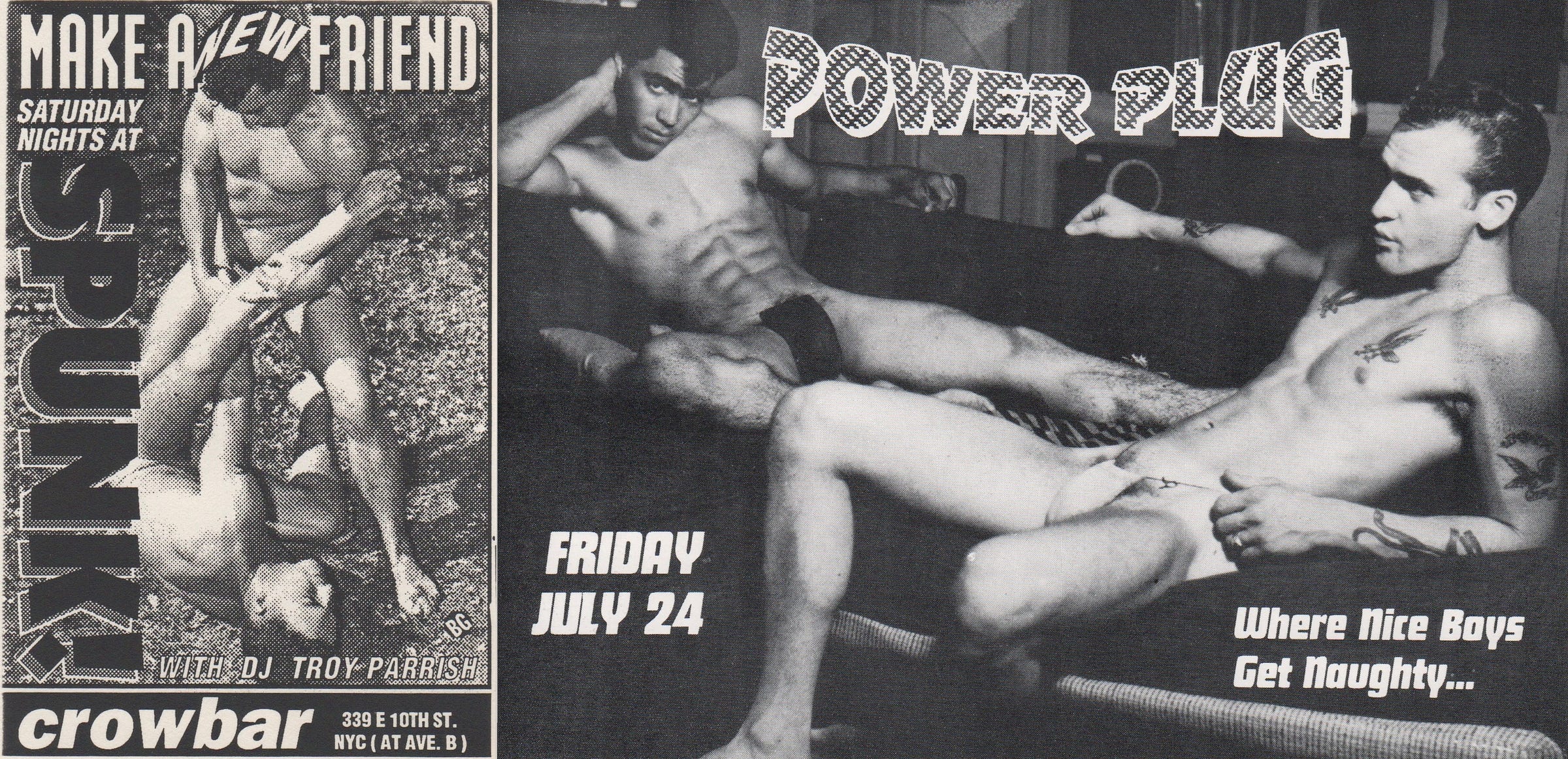

In a way, it seems like a hot guy is a hot guy, so why wouldn’t that go on forever? The only reason I’m well-acquainted with the charmingly not-so-innocent quality couched in images of all-American men without many clothes is because their hopelessly time-bound quality made them perfect choices to be used as kitschy invites to ‘80s club nights. If ‘50s and ‘60s nudes and near-nudes worked on some level 20 and 30 years later, and if they still work on some level 60 and 70 years later … why not forever?

Still, as an obsessive devotee of all things ephemeral and all things beefcake, I find it a compelling concept. Could these images possibly lose all relevance and power as generations are exposed to hardcore porn, or are distracted by self-generated prurient content?

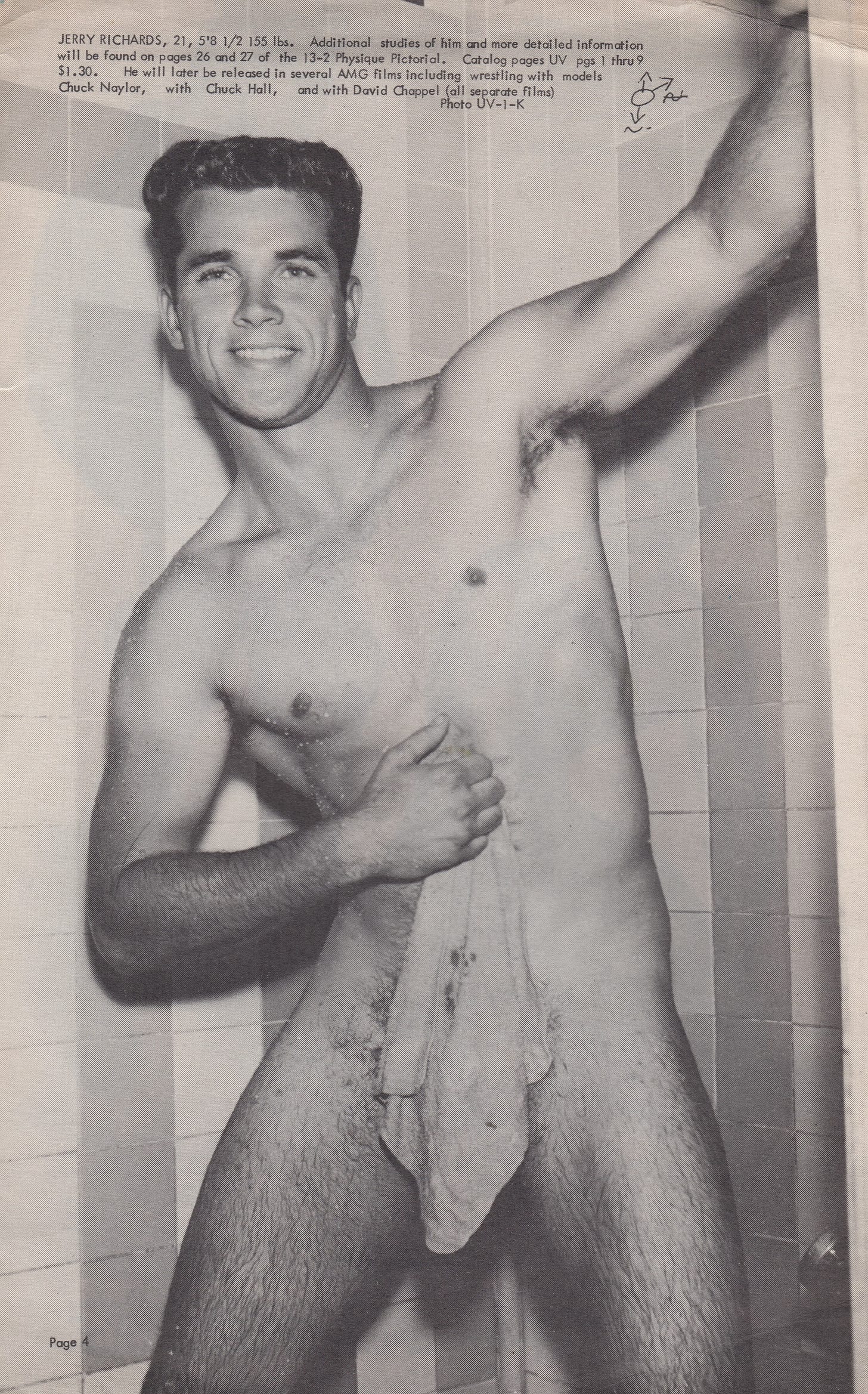

Since part of what has made retro physique photography so valuable up till now is its ephemeral quality — original prints and vintage magazines in good shape are prized — could younger people, who were not raised with magazines, and whose lives have been centered around all things digital, actually come to view ephemera as nothing more than analog debris?

As a passionate collector and archivist (show me your junk if you have vintage gay photos and magazines to get rid of, whether yours or your late uncle’s), it is my hope that our cultural attraction to ephemera will not itself wind up being an ephemeral trait.

One man who is attempting to preserve, share and pass along original queer ephemera is Barry Harrison, a collector-turned-purveyor who launched the site Homobilia nearly 20 years ago.

Inspired by his husband coining the term “homobilia” to describe gay photos, magazines and other paper goods, he went from selectively acquiring items he liked to snapping up anything he felt might be in need of a good home.

Granted, his buyers are mostly Generation X and older, but as long as Homobilia exists, it serves as not only a marketplace but a digital gallery and even a library, one with the stated goal of community-building and community-informing.

It’s a hot lesson, no matter where you turn on the site. But there is also a touching quality to these physical images that, in their decades of existence, have likely sustained so much touching of their own. Men have always been visual creatures, and still are. But we also used to be a lot more tactile, and nude photos surreptitiously purchased in the mail or nudist magazines cautiously bought on newsstands used to be — prior to the Internet, videos, Super 8s and loops — the only game in town.

I think that history is why homobilia can still prove to be such a lure to gay men. The photos are often art disguised as porn or porn disguised as art, but more than eye candy, they are also individual connections to the lives of the gay men who came before us.

Physique photography also lives on in the work of everyone from Fred Bisonnes (Advocate Men) to Bruce Weber, so in that way it is not only a glimpse into the lives of those who came before us, it is also a blueprint for what we find sexy today.

I spoke with Barry about his collection, his site and why homobilia matters more than the men who created it and posed for it probably ever realized.

When did you first encounter physique photography?

I think I came to it fairly late. I would say that I had an eye for physique photography when it was disguised as something else. I remember seeing pictures of wrestlers, or there was an advertisement for a gym in the newspaper, and it was like a Charles Atlas guy. I didn't really think of it as physique photography, nor did I even really think of myself as being gay. I just knew I was fascinated by those images. That goes back to when I was a little kid.

The first piece of homobilia I purchased was at a flea market in New York. There was a printing plate from a physique magazine. I don't know what the process is, but there were these wooden blocks, and then there's a copper plate on it or something, and it's etched. If you hold it the right way, you can see it, but if you don't hold it the right way, it's almost invisible.

“If you don't hold it the right way, it's almost invisible.”

It was just a physique photo from one of those magazines. I think that was the first real piece of homobilia that I purchased.