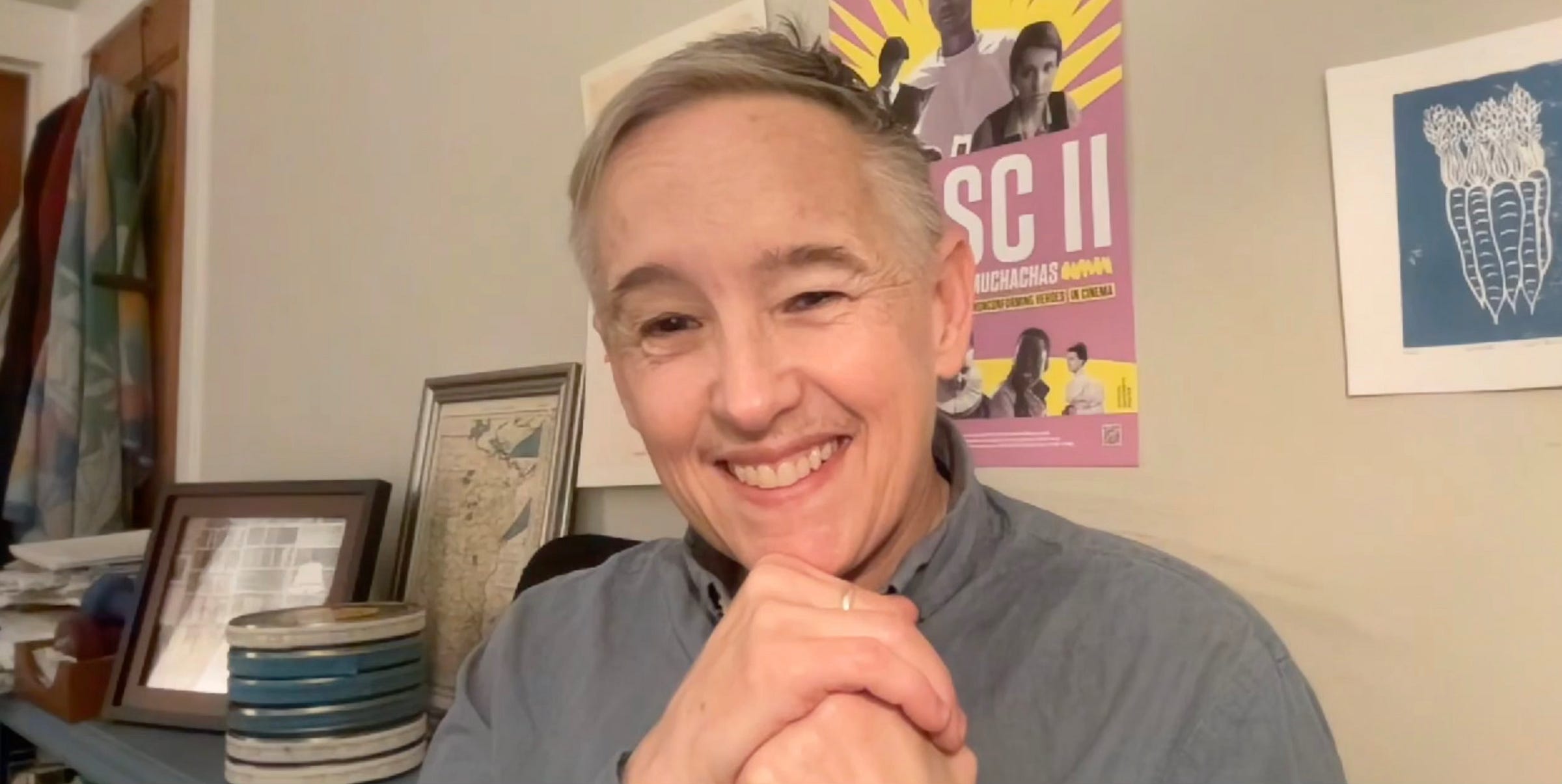

Movie Star: Bonding with Queer Filmmaker & Archivist Jenni Olson

The award-winning film preservationist's galvanizing landmark short '575 Castro St.,' which adds indelible imagery to Harvey Milk's voice, will next play the 2026 Berlinale

February 9, 2026

Jenni Olson is a movie star.

It isn’t that she acts, it’s that she has acted as a savior of film for the past 30-plus years.

A fellow midwesterner who became entranced by the power of the moving image early on, she curated the San Francisco International Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, founded the dearly missed PlanetOut.com, amassed a collection of films and movie ephemera so unique it was snapped up by Harvard and was behind the glorious Homo Promo, that ‘90s compilation of vintage queer trailers that captured forever how we once saw ourselves — as well as how we were once seen.

She also worked with Frameline, leading to her work on the indispensable Bressan Project, which has revived the legacy of gay filmmaker/pornographer Arthur Bressan of Buddies (1985) fame.

But on top of the mark she’s made as an admirer of film with an open mind and a discerning eye, Olson is a filmmaker in her own right. Her elegiac features The Joy of Life (2005) and The Royal Road (2015), like visual essays, are at once personal and an invitation to us to feel seen, to feel a creator understands some essential part of yourself.

I spoke with Jenni about her 2009 short doc 575 Castro St., which just played the 2026 Sundance Film Festival, and which will be presented February 14 & 15 at the Berlinale, which in 2021 bestowed upon her a special TEDDY.

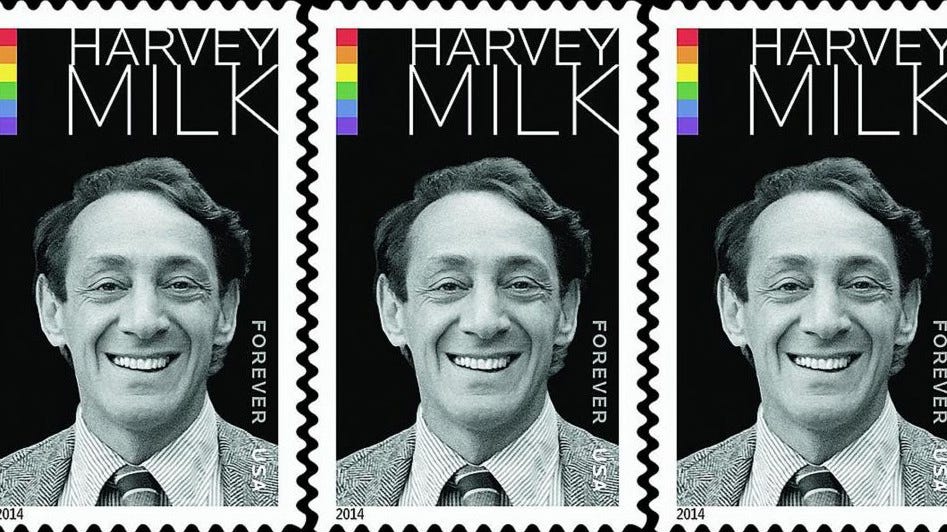

575 Castro St. uniquely marries footage taken on the set of the biopic Milk, which recreated Harvey Milk’s famed camera shop, with a recording the activist made in which he predicted his assassination and imparted his wisdom on the one thing he believed the LGBTQ+ community needs and that Olson’s work continually offers: HOPE.

How did film become so important to you?

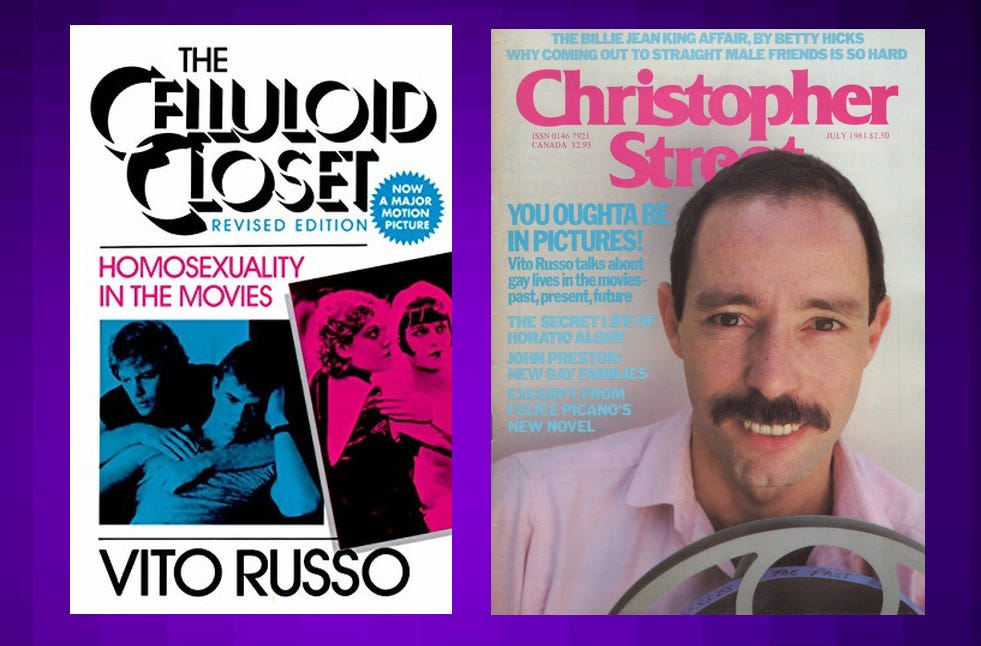

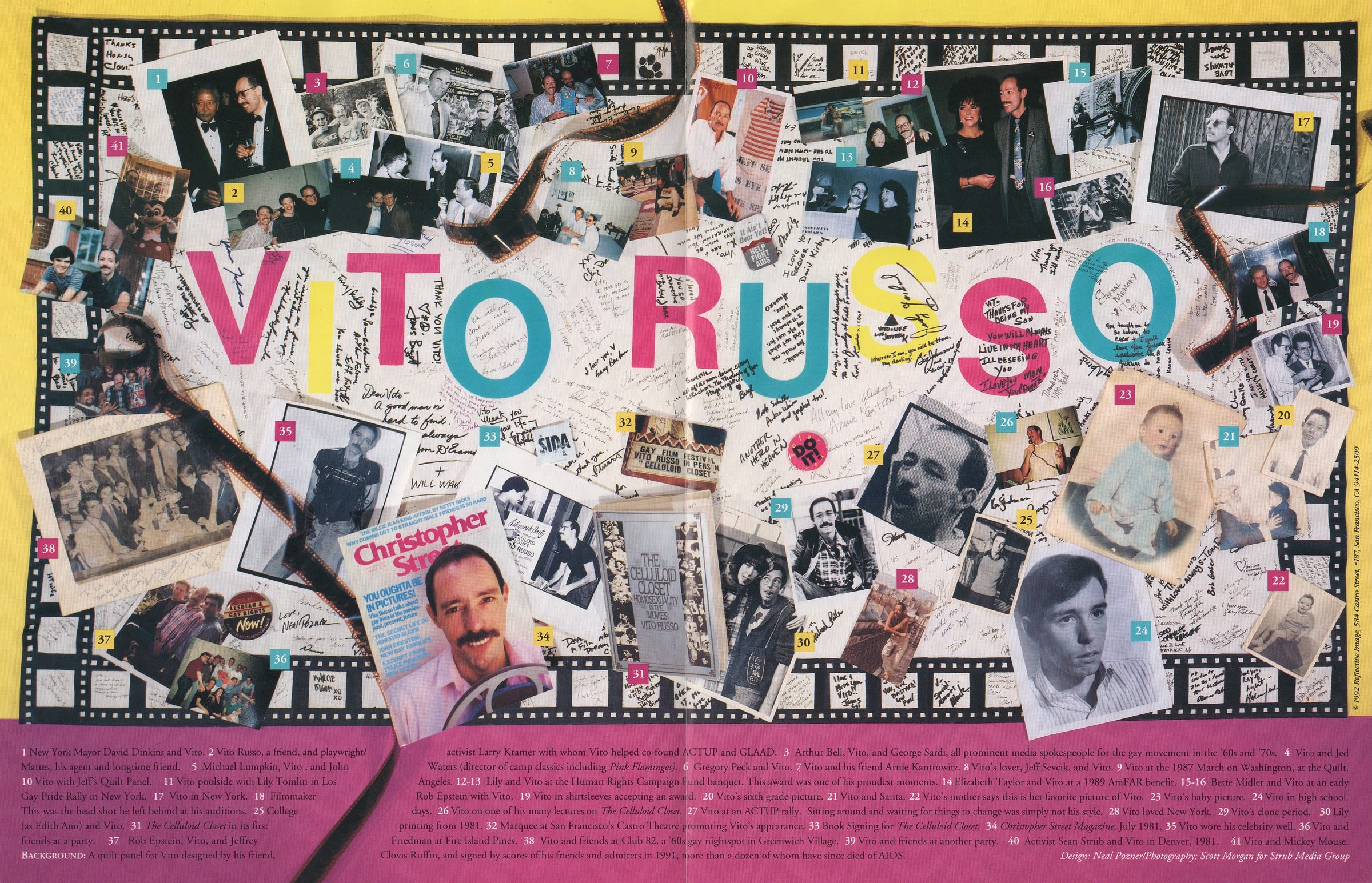

JENNI: Vito Russo’s book The Celluloid Closet … basically, I would say it changed my life. Maybe it saved my life. I read it in college and it was how I came out and was like, “I wanna see these films and I bet other people do, too.”

Were you more of a collector to begin with? When did you become an archivist, in your mind?

JENNI: I feel like it’s all of a piece. I kind of very quickly started collecting and … and I started programming, you know, doing this queer film series, which then led to being the festival co-director at Frameline and in San Francisco [at the Lesbian and Gay Film Festival]. I also simultaneously started being a film critic, reviewing films for the local gay paper.

I started collecting actual celluloid 35mm movie trailers. This was long before eBay and you had to subscribe to the collector’s monthly newspaper to buy and sell and trade things.

At the time that you were first collecting, did people think these things had value? Was it still an unknown field?

JENNI: I guess on the bright side, it wasn’t as quote-unquote valuable, and so I was able to buy all kinds of things.

If you think about it, it like the things that are the most ephemeral that seem like they are not valuable actually often turns out they are.

So, I have all these kind of incredible, special things. Like the thing I’m always most proud of is Queens at Heart (1967), four trans women in New York City talking about being trans. It’s just an incredible thing … It was something that hadn’t been written about in any literature of queer film history. And so it was this kind of a rediscovery of it. And then I worked with UCLA Film and Television Archive to get it restored.

That’s exciting because it’s something that was lost but no one knew it was lost. It just didn’t exist!

JENNI: Exactly. So, I felt even more proud.

How do films get lost? I think some people find it so hard to believe that any kind of film or video would become permanently lost. How does that happen?

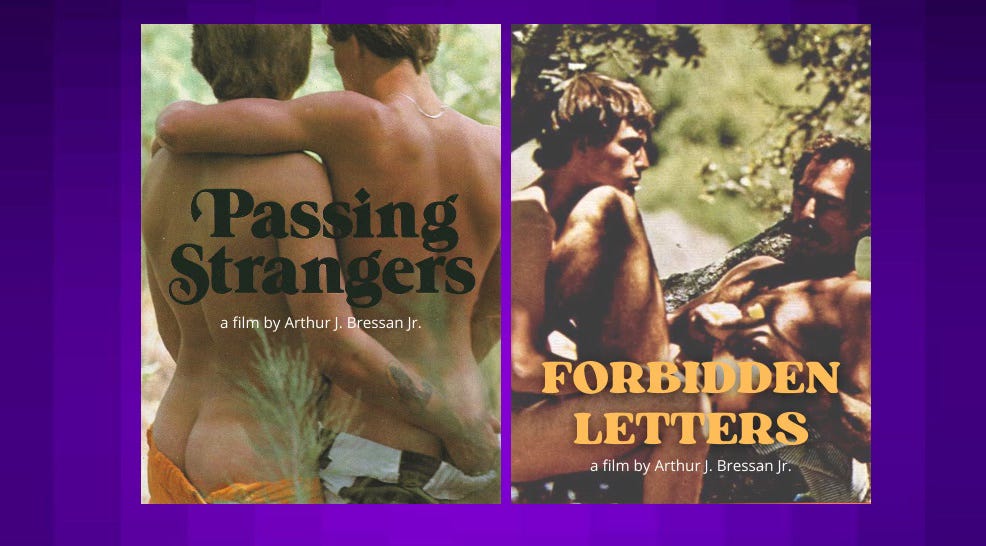

JENNI: One of the other things that I do is this thing called the Bressan Project, where I’ve worked to restore and re-release the films of Arthur J. Bressan Jr., who was an incredible gay filmmaker in the ‘70s and ‘80s. And actually, that’s a really great example.

He died of AIDS in 1987. His sister, who’s amazing, Roe Bressan, she actually donated all of his materials to Frameline, which was a really good thing. And when I was at Frameline in the early ‘90s, we had all that material, just boxes and boxes of stuff. But there was a point where we fell out of touch with Roe, and she was the rights holder as the owner of the estate. And so, we couldn’t really do anything with the material because we didn’t have contact with the rights holder. That’s one of the big ways that things will get lost or kind of fall through the cracks, even though we actually physically had the materials.

And then, in 2018 I finally figured out how to reconnect with her. And we just immediately started working on the restorations and re-releases, but all that time, Arthur’s work had really fallen out of availability. And so it has been even more exciting for it to come back. But I think these kinds of things happen all the time. But it takes individual people who care to put their time and energy into it. Because it’s not like there’s huge money to be made.

I find Bressan interesting. I came to him through Buddies, which is such an astonishing film.

JENNI: When I programmed my film series in Minnesota in 1987, I showed Buddies. Buddies was the second film I ever curated as a programmer. So that was my original introduction. Then, when I was at Frameline, we had all of the materials there. The whole project, there have been these just angels involved in helping make things happen because film restoration is really expensive. There’s a company called Vinegar Syndrome. This guy, [co-owner] Joe Rubin has just been particularly the angel of the project. He was like, “Yeah, sure, we’ll just do the restoration. We’ll do the new scan. Don’t worry about it.”And we put it back out, did festivals and a theatrical release, and then Blu-ray and digital. We’ve just kind of gone one-by-one through all of his films doing that. Gay USA, of course, which is from 1977, is an amazing feature documentary.

Then his adult films are like the most romantic gay porn you will ever see. His 1974 film, Passing Strangers, and 1979, Forbidden Letters. And then last year we did his films from the mid-’80s, Juice and Daddy Dearest. And yeah, they’re just fantastic. I mean, they are porn as well.

You’re not a gatekeeper who wants to find things and collect and hoard things. You’re someone who wants to put it out there. What’s the easiest way to see some of the things you’ve collected?

JENNI: I am a hoarder, but in a good way. I’m a generous hoarder, I guess. Well, I mean, was really lucky a few years ago that the Harvard Film Archive acquired the actual physical prints of my collection, which is all kinds of 35mm trailers and features and 16mm features and old TV shows and commercials and ephemeral things and, you know, all queer kinds of things. They actually have all the physical stuff and are taking care of it, which is really nice. and then some things are available in other ways, like, and like, like my trailer program, Homo Promo, the queer trailers of the ‘60s and ‘70s — stuff like The Boys in the Band and The Killing of Sister George. That’s available through Kanopy, which is nice. Queens at Heart is available through Kanopy. And I make a tiny bit of money through it, which is nice, like to, you know, maintain my addictions.

Now on social media, everything is kind of showing old trailers, old clips from movies, old shows. And I immediately think of things like Homo Promo and how exciting it was at the time because no one was doing that.

JENNI: It’s been really sweet, actually, on Instagram. There’s a bunch of accounts that share clips and stuff and particularly Queens at Heart has gotten so much circulation and it’s been nice when people tag me and, like, give me my little credit — that just feels nice. But it’s a cool thing and it’s cool that people and especially young people, but, whatever, everyone is so excited about our history.

You know that thing that we always say, “We have always been here.”

Visibility matters, and it matters even more when it’s moving images, I think. It makes it even more human and more relatable to people.

JENNI: Yeah. I work for GLAAD now. Vito Russo, who wrote The Celluloid Closet, was a friend and mentor and, you know, just such an amazing person. He was also one of the founders of GLAAD. And you know, [he championed] this whole thing of the importance of LGBT representation on screen, seeing ourselves. And it’s just so moving to me to be, you know, to get to be at GLAAD now.

And to segue to the thing that’s going on in my life right now, I have my 2008 short, 575 Castro St. that just had a really lovely screening at Sundance as part of the Legacy Shorts Program, and then it’s also at the Berlinale… It all feels like such an honor to have my little short picked out amongst so many films that they could show.

Its’s extra nice that 575 Castro St. is also available widely so everyone can watch it. You don’t have to be at the Berlin Film Festival.

It also has this very meta quality that, because I was commissioned to make it by Focus Features for the release of Gus Van Sant’s film Milk, which, you know, was such an amazing film and like went on to win Best Screenplay and Best Actor Oscars. I love my little, tiny movie, being associated with this, you know, huge, Oscar-winning film.

When you shot that film, did you know exactly what the concept was? Were you shooting it knowing you were going to use his voice?

JENNI: Yeah … my aesthetic as a filmmaker, my shtick, is that I shoot, I mean, generally the rest of my work, I shoot 16mm urban landscape exteriors that are very contemplative, very static. And the idea is that it is this kind of evocative background for the voice-over. In my other films, it’s my voice rambling on about queer things. But it is a very specific choice in my craft, and in the case of 575 Castro St., it’s this kind of almost light-and-motion study of what’s happening on the walls of the camera store … so that it foregrounds your ability to listen and that it enhances your emotional experience.

For the audio track, I had actually helped with the restoration of this cassette tape that Harvey had made to be played in the event of his assassination, which of course is quite powerful, you know, really intense to listen to. I feel very proud of it as a film and that it is really foregrounding him and his messages of how important it is that we’re out there and … 50 years later, I mean, you know, that we’re in the landscape that we’re in, which has, you know, so many parallels of being just absolutely under attack from the right and this political fear-mongering that is such obvious political fear-mongering. Yeah.

It’s so sobering that he felt the need to record what should happen if he were assassinated. And then to have him give instructions for what Mayor Moscone should do without realizing that he would die at the same time … I just find it so chilling to listen to.

JENNI: Chilling is exactly the — it takes your breath away, the whole thing. I mean, I’ve listened to it, you know, I don’t know, 50 times, and every time is so powerful. And he was just such a great speaker. He’s so inspiring. I love that — spoiler alert — that it ends with his “you gotta give ‘em hope” line, particularly in relation to young people and the importance of being out.

I always wondered this about him, but I think watching your film even more so, it makes you wonder what he would have made of everything that came after. Because he had such a vision of the way things should go. And it makes you wonder, like, how would he have reacted to AIDS, to gay marriage, to like all the different fights that we’ve had, gender, there’s so many things.

JENNI: It’s interesting that you say that; it makes me think of something that, and this is slightly digressive, which is how I am, but one of the best things when I put the film out, my kids were in middle school at the time, and one of the best things was that I got to go every year to their school and give a presentation to the kids about who Harvey Milk was. And again, like, I’m saying how important it is for young people to be like, “Hey, here’s this guy. He was gay, whatever. He was a hero.” All the kids there who are gay, are figuring it out, are like, “My God, this great guy was a hero.”

But one of the things that I talked about a lot was how Harvey as being on the board of supervisors, he was this very intersectional thinker. And he talked about everyone’s rights, and he talked about all the different communities in San Francisco. And so, I am thinking about right now, and particularly what’s going on in Minnesota, and the sense of intersectionality between political fear-mongering around immigrants and political fear-mongering around trans people. And that if you step back, it’s so completely obvious that that is what this is. And that they are the same thing, picking a group of people that people are a little afraid of or don’t understand and then filling the vacuum with hate and fear.

So, I think of Harvey would be like, “This is bullshit.” That’s what comes to mind when you, when you mention that.

What do you think you’ve been doing to give people hope? Because I feel like your films are in a continuum of giving people hope.

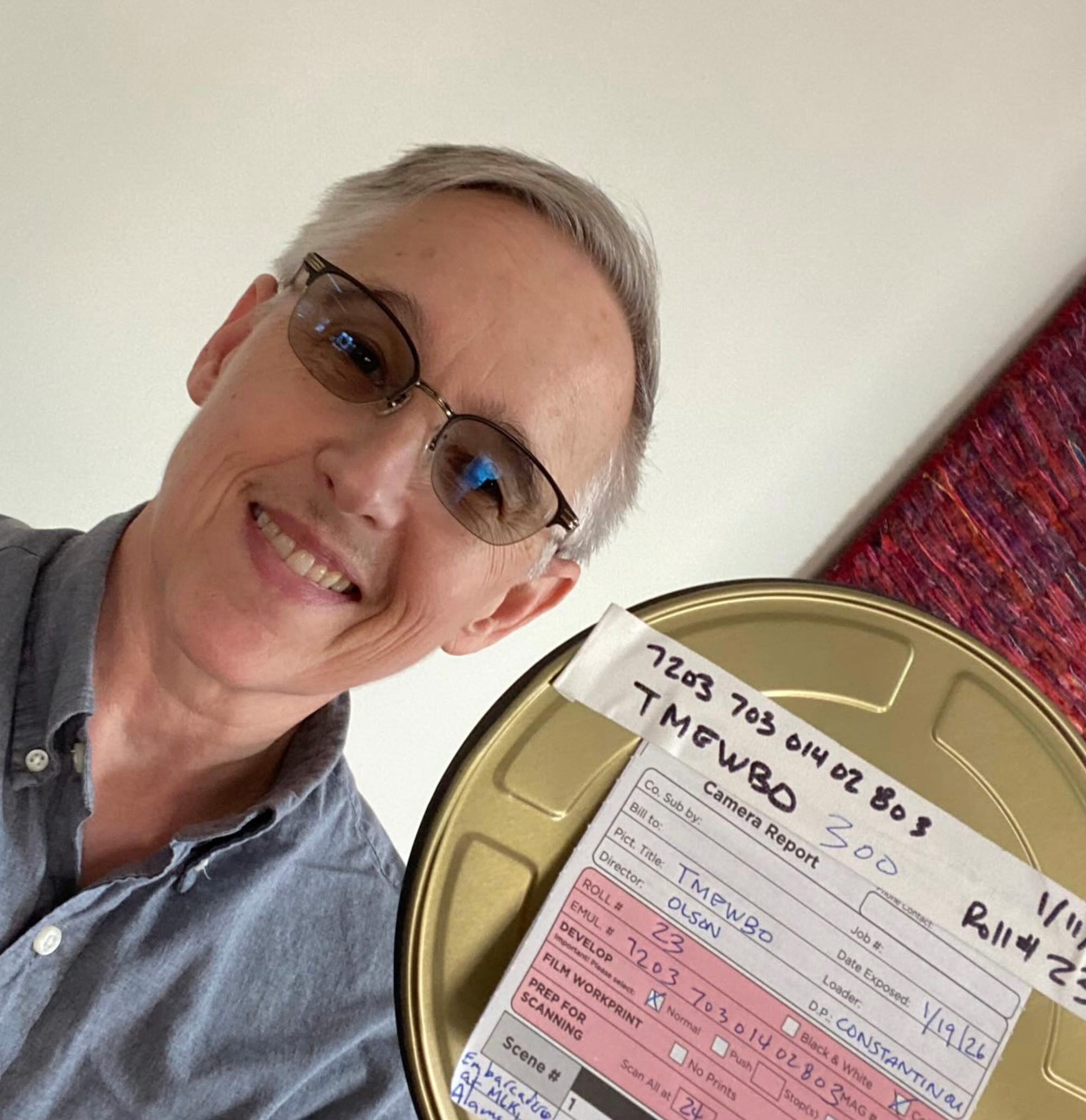

JENNI: Sometimes I think my whole shtick is to be extremely humble and maybe a little too humble, but I don’t know. I mean, I have a few different thoughts about that. Well, I’m working on a new film right now that should be done by the end of this year and hopefully will premiere early next year, Tell Me Everything Will Be Okay. And it’s interesting because every time I say that title to people in these times, you know, they’re like, “My God,” but the truth is that title and the film itself is not about what’s going on in the world and this political moment, even though of course you immediately think of that.

My work does end up having these kinds of, I don’t know, social justice components.

Mostly, it’s about trying to connect with people on a much more personal level and a much less literal, direct, social-justice level. It’s funny. I’m suddenly feeling very inarticulate about my work.

But it does connect back to what we were saying about the importance of seeing ourselves represented on screen. The main drive in my work is always about speaking as someone who’s gender-nonconforming.

And so the most important thing to me is that folks who are gender-nonconforming or folks like myself are like, “My God, I’m seeing myself on screen and this is speaking to my experience and I feel less alone and I feel entertained.”

And, you know, that we’re all connecting across our common humanity, if you will. And just the last thing about it, and which is the thing that I do say that I think provides hope every time I have a microphone in my hand, is … amidst everything that is happening and especially the attacks on trans people, like, we have each other as a community — and we’re amazing. And that is the thing that we have to hang on to.

On that tip, can you talk a little bit about your Queer Photo Archive? I just saw it and I thought it was amazing because it was just these photos of all these butch women without really any explanation of what the photos were from. But that’s all you need. You see that and it just tells such a story.

JENNI: Thanks for asking about that. This is another of my obsessive hoarding things. The Queer Photo Archive is a collection of original 8”x10” wire-service photos going back to like the ‘30s, ‘40s, ‘50s, ‘60s — I even have some from the 1920s. I started collecting them as these examples of people who were arrested. And the headlines are, one of the most significant ones is this person, Jack Starr. And the headlines were, “He’s a She” — they’re not nice headlines, mostly. But what you realize cumulatively is that you have all of these AFAB folks — Assigned Female at Birth People — who lived as men and then would be arrested at any given moment or whatever, be revealed, like, they were not assigned male at birth. And I mean, it’s super interesting to imagine myself, I mainly identify as butch, gender-nonconforming. If I lived 100 years ago, I couldn’t go around like this and just be like, “I don’t have to explain myself. And I’m not going around in a dress.” You would have to choose.

It’s so interesting how our identities evolve over time and in history. What options we have available to us in terms of how we describe ourselves, how we experience ourselves, how we are reflected back to ourselves in culture or not reflected back.

It’s especially amazing to see these images from 100 years ago and be like, “This totally looks like someone I literally saw yesterday at the queer bar.”

I have done some research and actually, the main one that I had started with and did a ton of research on is this guy, Jack Starr, who was in Montana in ‘30s and ‘40s and was repeatedly arrested over literally decades. I worked on an HBO Max series a few years ago called Equal that’s still on and we did a segment on Jack Star with Theo Germaine playing Jack Starr.

Do you, in your work, find that gay men are usually interested in gay male films and lesbians are usually into lesbian films and there’s not a lot of crossover? Has that been changing?

JENNI: Um, I guess maybe it’s changing a little bit. I think mostly not. I’m always reminded of my friend Alonso Duralde, the queer film critic. And I just remember him saying to gay men, “Like, would it kill you to see a lesbian film?”

Like, go see “Go Fish,” you know, just see something. But there is more of a mainstream appreciation of queer stories, I think?

JENNI: Yeah, yeah, for sure. It continues to be that we, like, we get, you know, a few big queer movies every year.

We “get” them. It’s true. It feels like we’re allowed, “Okay, you’re getting Heated Rivalry this year and that’s it for you.” What’s next?

JENNI: Mainly, I’m really focused on this new film, Tell Me Everything Will Be Okay, that will be — God willing — be done at the end of the year and coming out in 2027, and my full-time job at GLAAD, all the work that we do trying to make the world a safer place.

We have our work cut out for us.

Well, but I will just tell you — everything will be okay.

JENNI: That’s exactly why I came up with the title of the film. I want that. We all want to reassure each other. Thank you. Thank you. ⚡️