Robert Joy's Big Break Was a Big Choice

The out actor opens up about his 50-year career

October 8, 2025

Out actor Robert Joy is one of the guys who was in the enormously entertaining 2012 documentary That Guy … Who Was in That Thing, which profiled 16 character actors with familiar faces, yet who never became household names. A recent flight Joy took resulted in a real-life reenactment of that premise.

“This couple was on the airplane yesterday from Virginia somewhere, a young man and a woman. The guy was smiling at me across the aisle, and I thought he was trying to be friendly,” he recalled in an October phone interview. “Then, just as we were landing, his wife said, ‘Were you ever an actor?’ They couldn’t remember where they knew me from.”

They asked the dreaded question: “What have you been in?”

An actor since 1972 with nearly 150 TV and film credits, not to mention a slew on the stage, he offered, “It’s been a long time. How about CSI: NY?” They’d never seen it. That was something their parents watched. When this happens, he often tries Desperately Seeking Susan, but no dice. His current gig on the MGM+ sci-fi series From might be too recent to have sunk in.

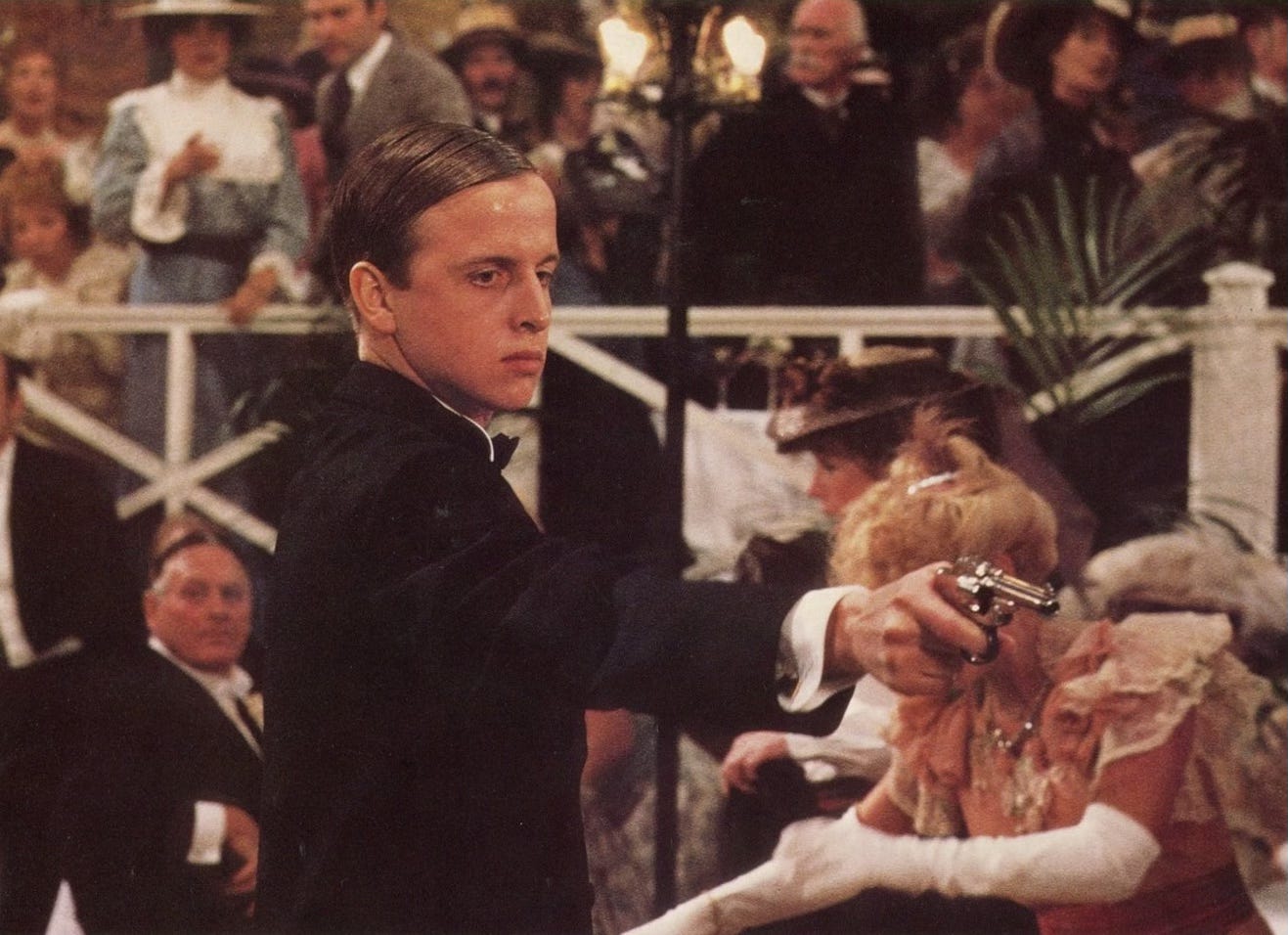

It’s easy to have empathy for audience members who kinda know him, and for Joy, for kinda not knowing which of his credits to brandish. This is a guy who got stabbed conspiring to sell drugs with Burt Lancaster, shot Norman Mailer, came out to Dianne Wiest, made out with Madonna, hunted zombies for George Romero, got murdered by Barbara Bain, impersonated Stephen Hawking for laughs … and hit all the right notes in his real-life partner Henry Krieger’s most darkly adventurous Broadway musical.

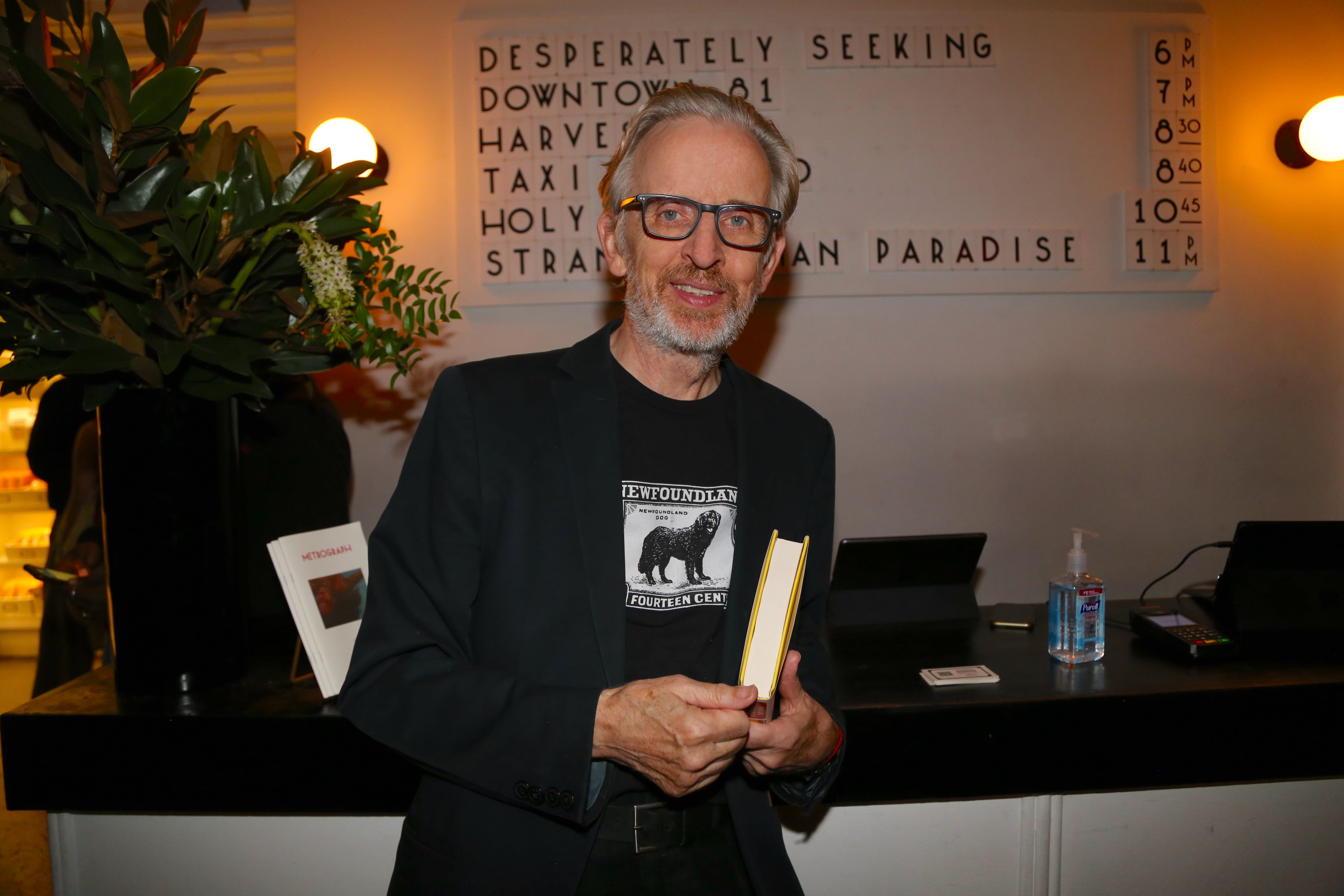

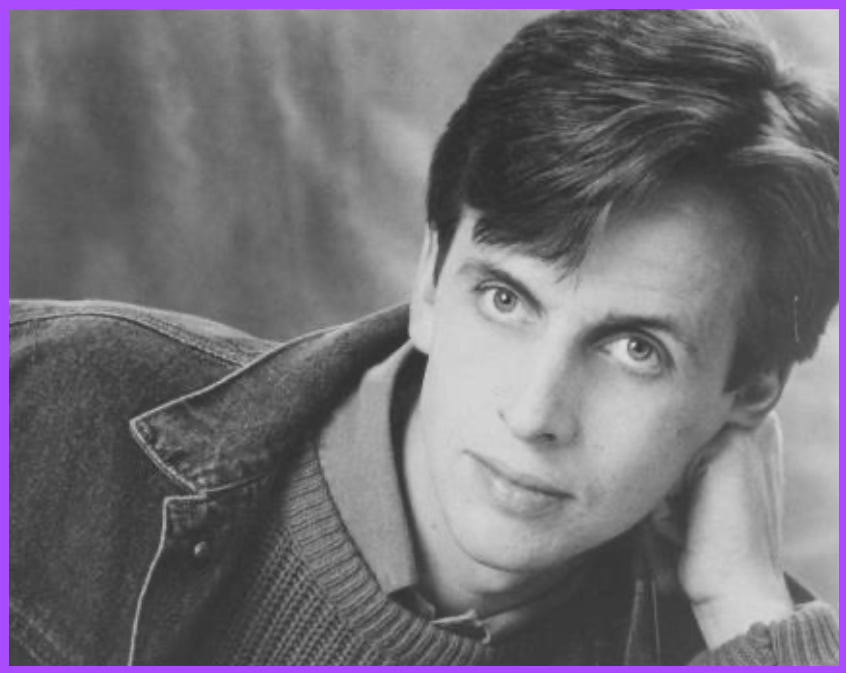

Speaking of which, I was fortunate enough to first interview Joy backstage at Side Show on Broadway in 2014 for my book Encyclopedia Madonnica. The entire interview was narrowly focused on Desperately Seeking Susan, in which he plays enigmatic Susan’s puppy-eyed punker boyfriend Jimmy. Recently, I attended a 40th-anniversary screening of the film and had encouraged the director, Susan Seidelman, to invite Joy, a Canadian who now lives in NYC. He came, we reconnected and I thought our conversation should be continued.

He’s played dirtbags, been a cut-up and slipped into the skin of freaks, always effortlessly radiating offbeat New Hollywood charm. I personally think this actor, always so adept at carrying a B story, has been the A story all along.

Was there anything about your childhood in Canada that hinted you’d eventually become an actor?

ROBERT: I wouldn’t say so at all. I remember in high school, for example, I went to an all-boys Catholic school, and the principal had this idea that — he was a very musical guy, and he wanted us to do Gilbert and Sullivan. I was in the glee club. He said I was going to sing. I can’t remember what it was, maybe The Mikado or something. I thought, “Really?” He brought me into the audiovisual room, which was like a tiny theater room in our high school, and put me on the stage and said, “Well, sing this.” He gave me something to sing, and I was paralyzed. It seemed really unfamiliar and uncomfortable.

But I got over that! [Laughs]

I guess you would call it transformative. I enjoyed the whole community thing of it. My brother and I are very close in age. He’s just a year older than me. So we formed a a social unit. It wasn’t automatic to make friends outside the family, and theater was amazing for that. What was revolutionary from our point of view was that the next year, when we did The Pirates of Penzance, they involved the girls from the all-girl high school, and suddenly, I was actually socializing with girls, which had never happened. It opened up my world in a big way, socially.

So, you became more interested in acting in college?

ROBERT: When I went to university, I studied English, and I figured I’d be a teacher or maybe a professor.

What changed that?

ROBERT: Here’s what changed that: In the final year of university, I had been doing acting with the university people, and there was a very active community theater in St. John’s, Newfoundland. I did some Shakespeare and really enjoyed it.

In 1969, I think, I got a job as a counselor-in-training, they’re called. It’s not quite a counselor, but it’s not a camper, either, at a canoe-tripping camp for boys in Ontario, Canada. And the only reason I got it, my younger brother had been a camper there for years, and he was always having an amazing time, so I thought, “That’s a good summer job.”

I got to be close friends with one of the other counselors-in-training. I think there were three of us who hitchhiked from Algonquin Park, Ontario, to Stratford. In-between the July campers and the August campers, we got, gosh, I don’t know, a week off maybe, or something like that, and we hitchhiked to Stratford. That was transformative because we went to Stratford, saw a few amazing productions, and the one that really sticks out was Satyricon.

“It was wild and sexually liberated.”

When I think about it, it was wild and sexually liberated. Then, in the world around the festival, there was this guy, Cedric Smith, who was, I guess, what you’d call a hippie. He was a good actor, and another guy sang and they had music in the coffee house there. Their group was called Perth County Conspiracy. Perth County was the county in Ontario that Stratford is in. They were iconoclastic, funny. I remember one of them put out a candle with his thumb and forefinger. This was wild for me.

When I got back to St. John’s, Newfoundland, after that whole summer, I was fired up to do more theater. I still wasn’t choosing it as a profession necessarily, but I was really fired up. So the next few community theater things made a big impression on me. We did some, I remember doing a production of Charley’s Aunt, where I didn’t even know that the part I got in the auditions was the comic lead. Then, when I did it, the audience is falling about, and my part is clearly the part, and I got really excited about that, too.

The Newfoundland Traveling Theater Company in 1972 did a British farce at night and a nonmusical version of The Wizard of Oz in the daytime for kids. And that was the big thing. So a bunch of my contemporaries and I did that tour. The actual director was a transplanted Brit named Dudley Cox. He instilled in us one of the basic tenets of being a professional actor, which was: It doesn’t matter what day you’re having, what mood you’re in, you have to do the show, and you have to keep up a standard. I remember being impressed by that. The difference between just doing it for fun and doing it because you have an obligation to keep up a standard — that was huge.

And then I fell in love with one of the actors in the company, and we ended up, by the end of it, being a couple. He was a very funny man, a genius, and he’s still a genius. His name is Andy Jones, and Andy and I decided to move to Toronto and see what we could do in the acting world. We moved up to Toronto and made ourselves available for auditions.

Being gay and pretty open like that in the early ‘70s must have had its challenges … ?

ROBERT: It was all very exciting and transgressive because it involved us living together at a time when ... For example, when we found an apartment together eventually, we had to perpetuate the whole roommate fiction. “We’re just roommates!” And I remember my parents, by this time, had moved to Niagara Falls. I remember we got some furniture from my parents’ apartment, and it was actually the bunk beds that my brother and I had slept in growing up.

That’s no use! [Laughs]

ROBERT: No. So we moved the bunk beds. Andy and I would sleep in one of the bunks, but we made sure to mess up the other one. We called it the decoy, or something like that. So in case the super had to come in to fix something, he wouldn’t see just one bed messed up. We had to keep up the fiction. And actually, a single bed is of great use for young gay couples. You don’t need a lot of real estate.

“A single bed is of great use for young gay couples. You don’t need a lot of real estate.”

Was being closeted in that way something you thought about a lot at that time?

ROBERT: Oh, yeah, definitely. Andy got a job with a really cool theater company in Toronto called Theatre Passe Muraille that ended up launching him before it launched me. I went back to university. I got accepted to the Graduate Center for the Study of Drama at the University of Toronto.

Being gay in our careers was not something that was on our minds one way or the other. Once you were in a production, it was easy to be honest with your coworkers — “Andy and I are a couple.” But you wouldn’t spread it around. It was an understanding that there was a discretion built in that nobody wanted to publicly declare themselves gay or anything. But the understanding was that you could do anything. I mean, that was the whole thing. You didn’t want to be pigeonholed for gay roles. You didn’t just want to do gay roles. And there weren’t many gay roles, right? I remember how brave it seemed to us when Brad Davis did Midnight Express and Querelle, which was a gay fever dream.

The gay iconoclasm was in the theater world before it was in television and film. I remember Fernando Arrabal and these European absurdist playwrights were doing really exciting and transgressive theater. Being in the theater, you didn’t care about being out, but you didn’t want it to be out in the TV and film world.

How did you become involved with the famous comedy troupe CODCO?

ROBERT: I had applied for the Rhodes Scholarship a couple of times from Newfoundland. There’s a tradition in Newfoundland. It’s an unspoken norm, as opposed to a rule, that a Catholic kid would get it one year and then a Protestant kid would get it the next year. It was just understood. I applied and didn’t get it in the Catholic year. And then I applied in the non-Catholic year and didn’t get it. And then Andy and I fell in love and moved to Toronto. This was something that I kept from my parents. As far as my parents knew, Andy and I were friends that wanted to be crazy and go to Toronto and try to be actors.

Andy was somebody that my mother wished I wasn’t friends with because she thought I was a candidate for the Rhodes Scholarship. She wanted me eventually to be the lieutenant governor. She thought this was the wrong road to take if I’m going to be a pillar of the community.

Anyway, my mother put some pressure on me. She said, “Apply one more time. It’s the Catholic year again. Just apply one more time.” I said, “Mom, I’m up in Toronto. I’m studying drama, and I’m thinking more in terms of not going to Oxford.” She said I could apply this last time, so I did. And of course, I got it. And that made a whole bunch of things happen.

One thing that happened is this guy, Gillie Fenwick, had directed me in Charley’s Aunt back in St. John’s. And as I told you, it was big for me. It was an exciting influence. His friend, Joseph Shaw, had become a noted actor and director in Ontario and was looking for somebody to play the same part in a professional production of Charley’s Aunt in Ontario. I quit the graduate center to do that, to play the same part, Lord Fancourt Babberley, in a professional production because I knew I was going to Oxford the next fall, and that was exciting for me. And so I ended up going to Oxford and had an academic year in Oxford, but after two terms at Oxford, which I was really enjoying, I get a call from Newfoundland that in my absence, that fall, while I was at Oxford, Theatre Passe Muraille had come to know a bunch of Newfoundland actors that had come up to do the same thing that Andy and I had done, come up to Toronto, trying their luck. And they had auditioned for Theatre Passe Muraille, and there were no parts that were right for them. But the artistic director, this guy Paul Thompson, said, “You guys are very interesting, unusual people, and I can tell you got something going on. So here’s $300 of seed money. I’ll give you a space. Why don’t write a show?”

And so they wrote a show called Cod on a Stick that basically changed everything. So they wrote this vinegar-satirical comedy show. This is all without me, and actually without Andy. Andy was on a different path. It became a sensation. They were suddenly being compared to Second City. Have you ever heard of a thing called the Newfie joke?