The One & Many Jimmy James Reenacts Like a Woman Should

The world's greatest Marilyn Monroe tribute artist talks about his origin story, his fandom, his craft & the career he was destined to have as he prepares a revealing documentary

October 26, 2025

When I was a baby gay, I chose to attend college in Chicago, the cosmopolitan city nearest to my small-town Michigan home, an environment suitably far away from my old life. See, I wanted to be in a place where I could get a little lost, kiss other boys, find gay porn and see drag queens.

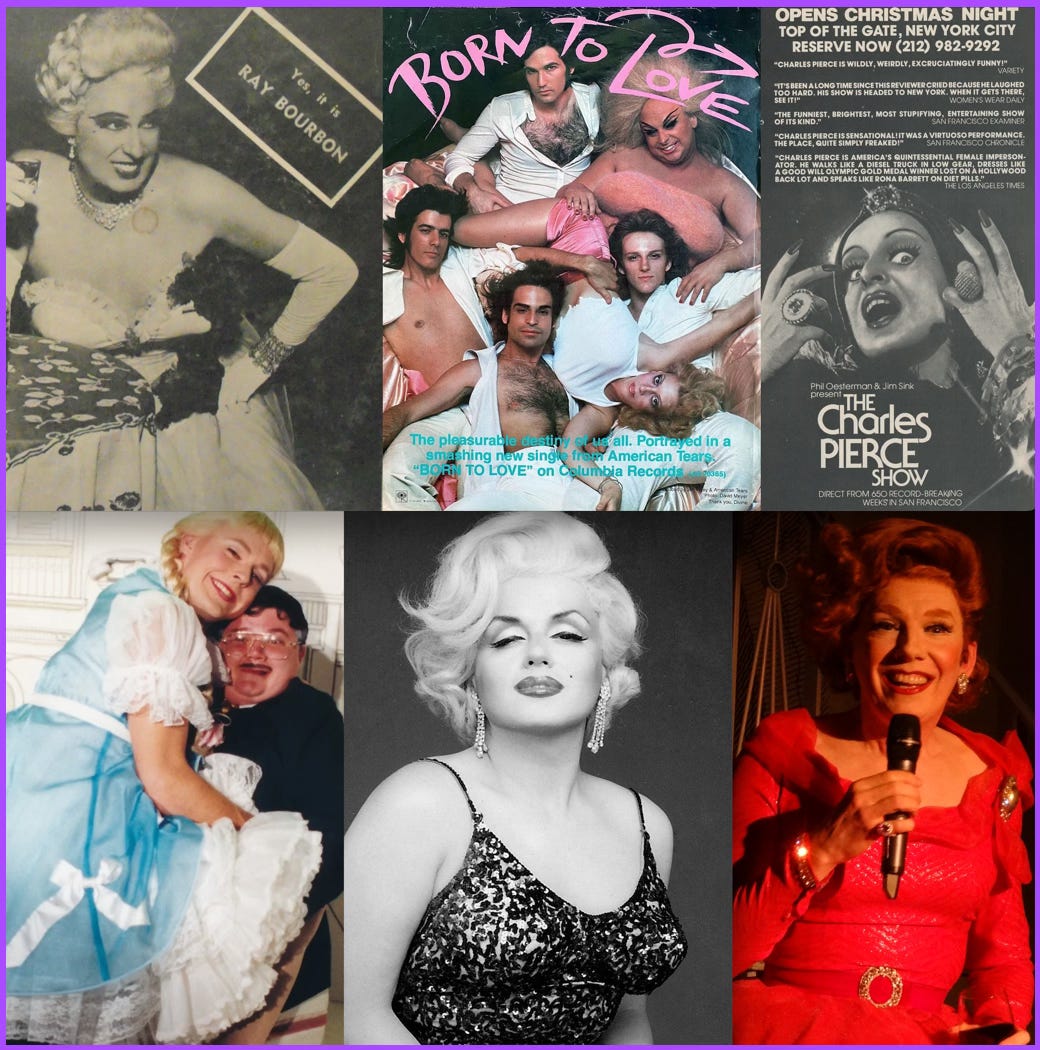

I wound up getting my fill of drag early on. By the late ‘80s, the drag scene was already glutted with lazy lip-synchers in the wake of geniuses like Ray Bourbon, Charles Pierce and Divine, to name a few.

But there were three drag artists I witnessed in person in my formative years whose talent I’ve never forgotten: manically funny Varla Jean Merman in the mid-‘90s, high-concept high priestess Lypsinka a bit before that and, before both of them, the incandescent Jimmy James, the so-called Boy Who Was Marilyn.

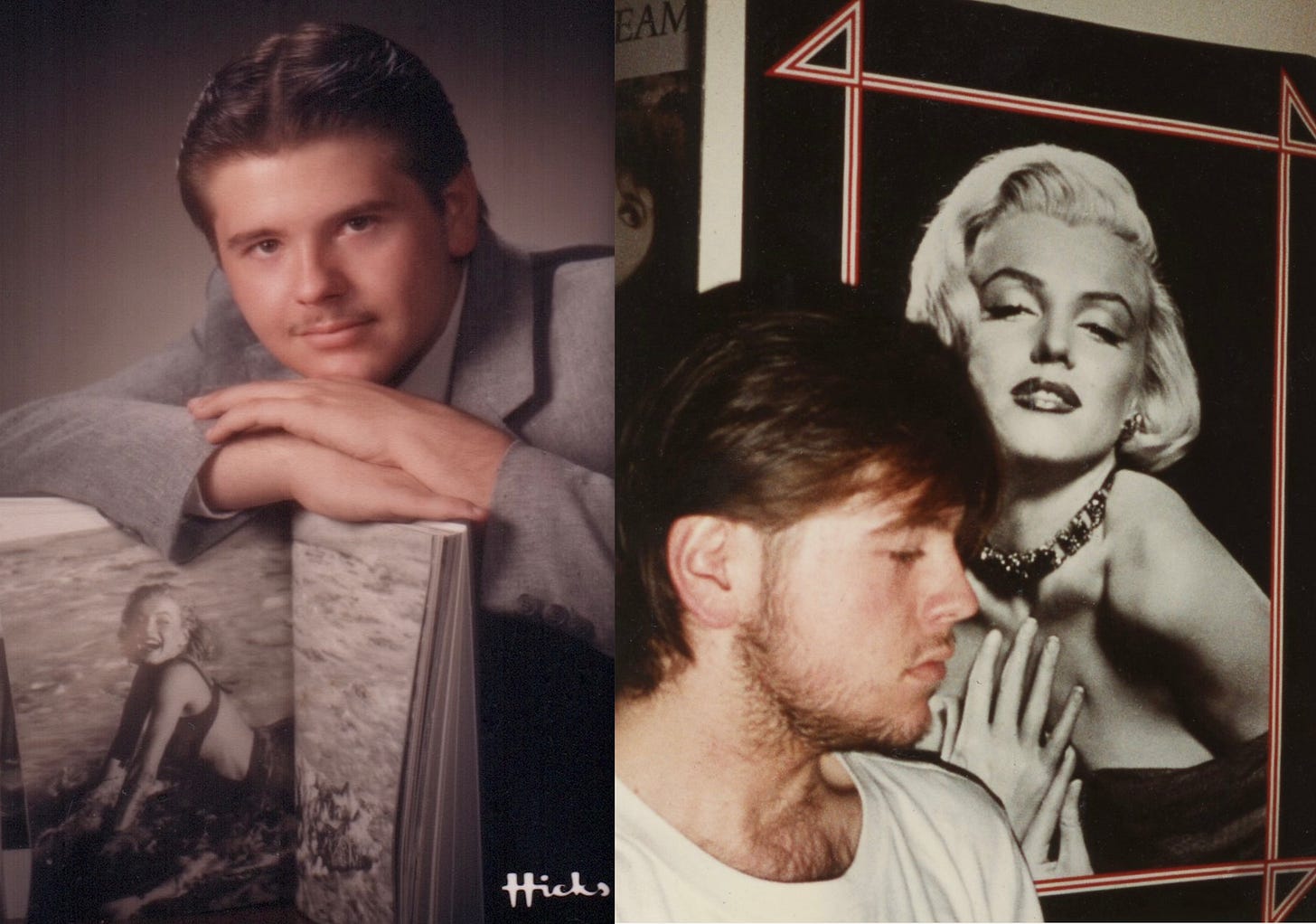

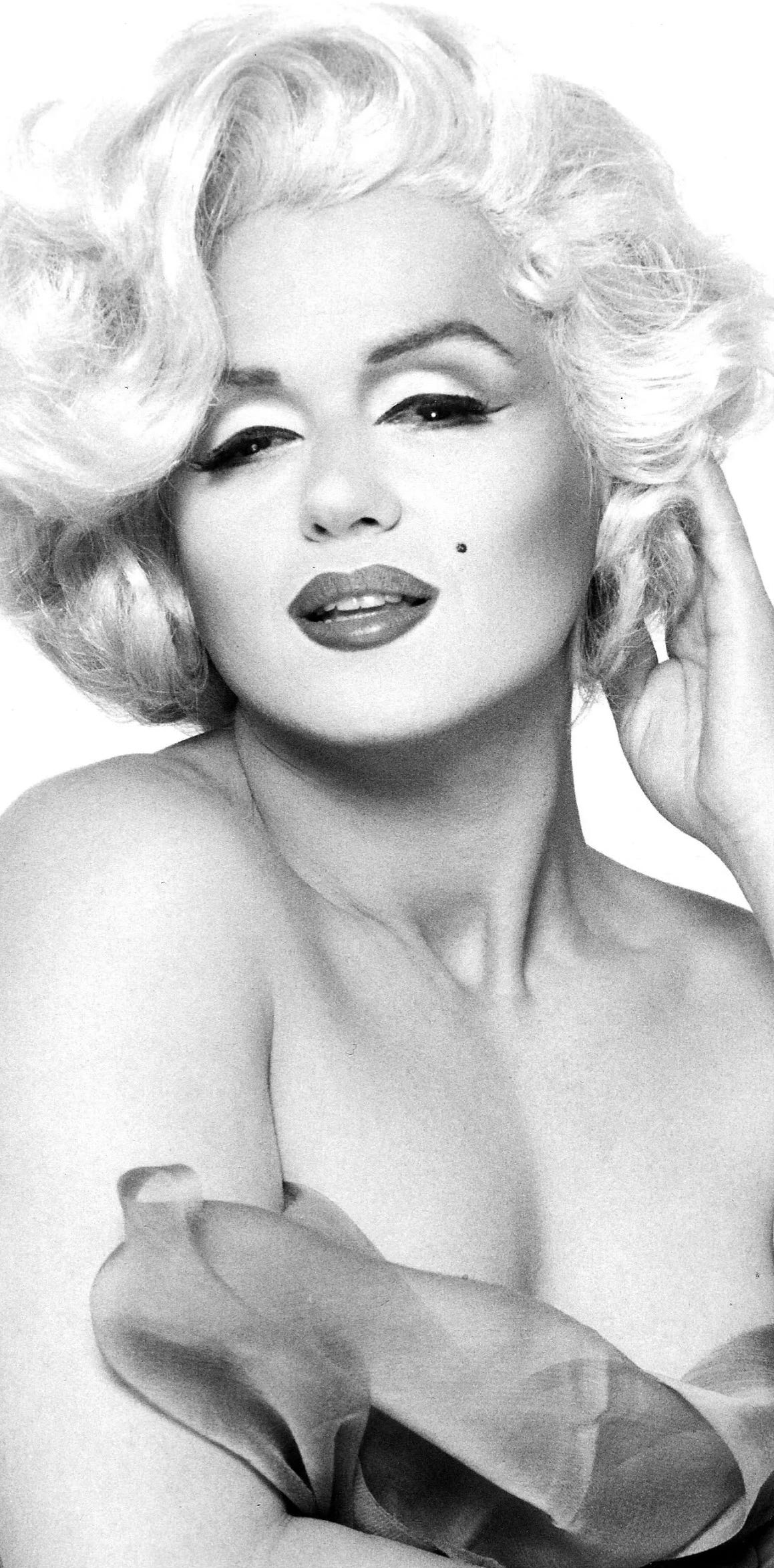

Like so many other gay teens who had come of age in the ‘80s, I was obsessed with Marilyn Monroe. Her image was all over retro posters sold at kitschy stores in every mall in America, she was seemingly Madonna’s spiritual godmother and Gen X was always enslaved by the fancies of the Baby Boomers, whose tastes have dominated popular culture by virtue of their overwhelming numbers.

“I’m meeting somebody. Just anybody handy. As long as he’s a man.” — Marilyn Monroe, “Niagara” (1953)

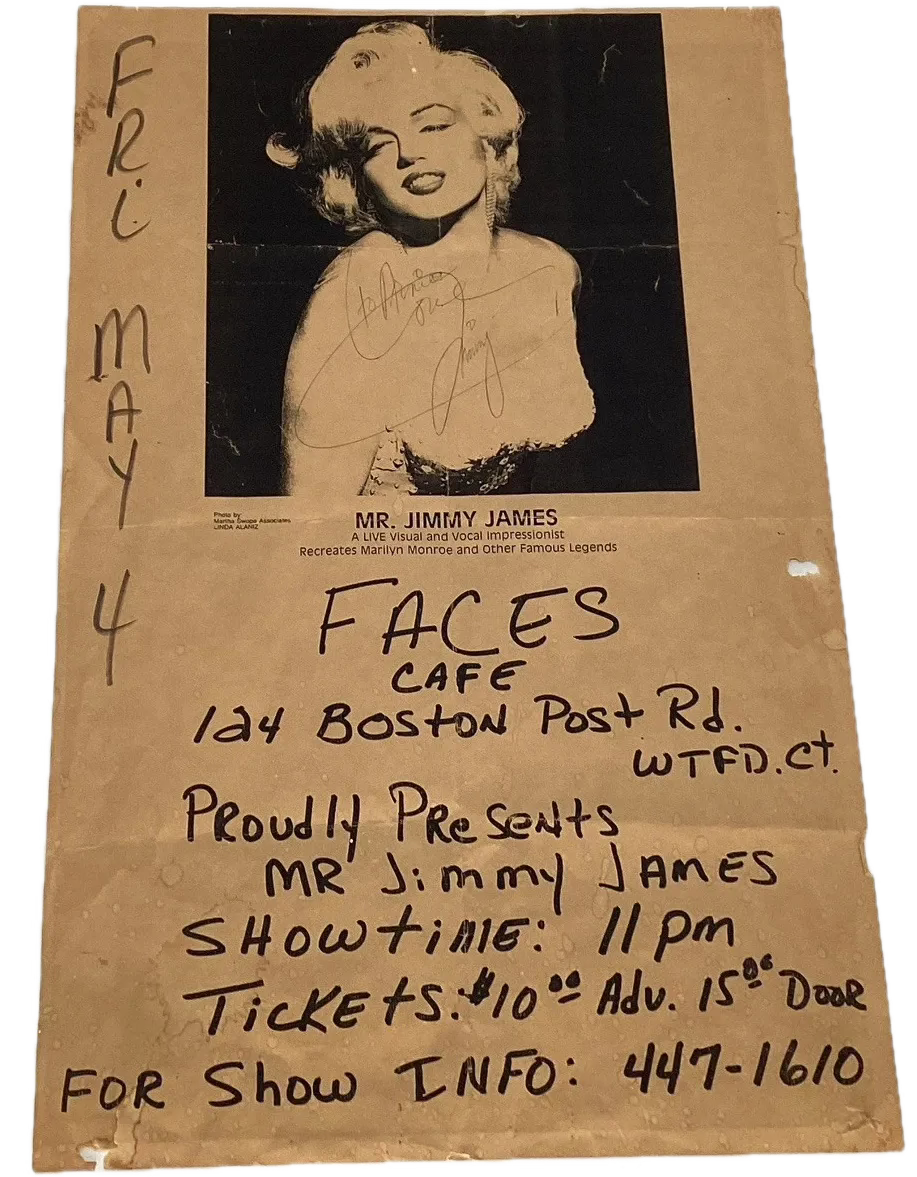

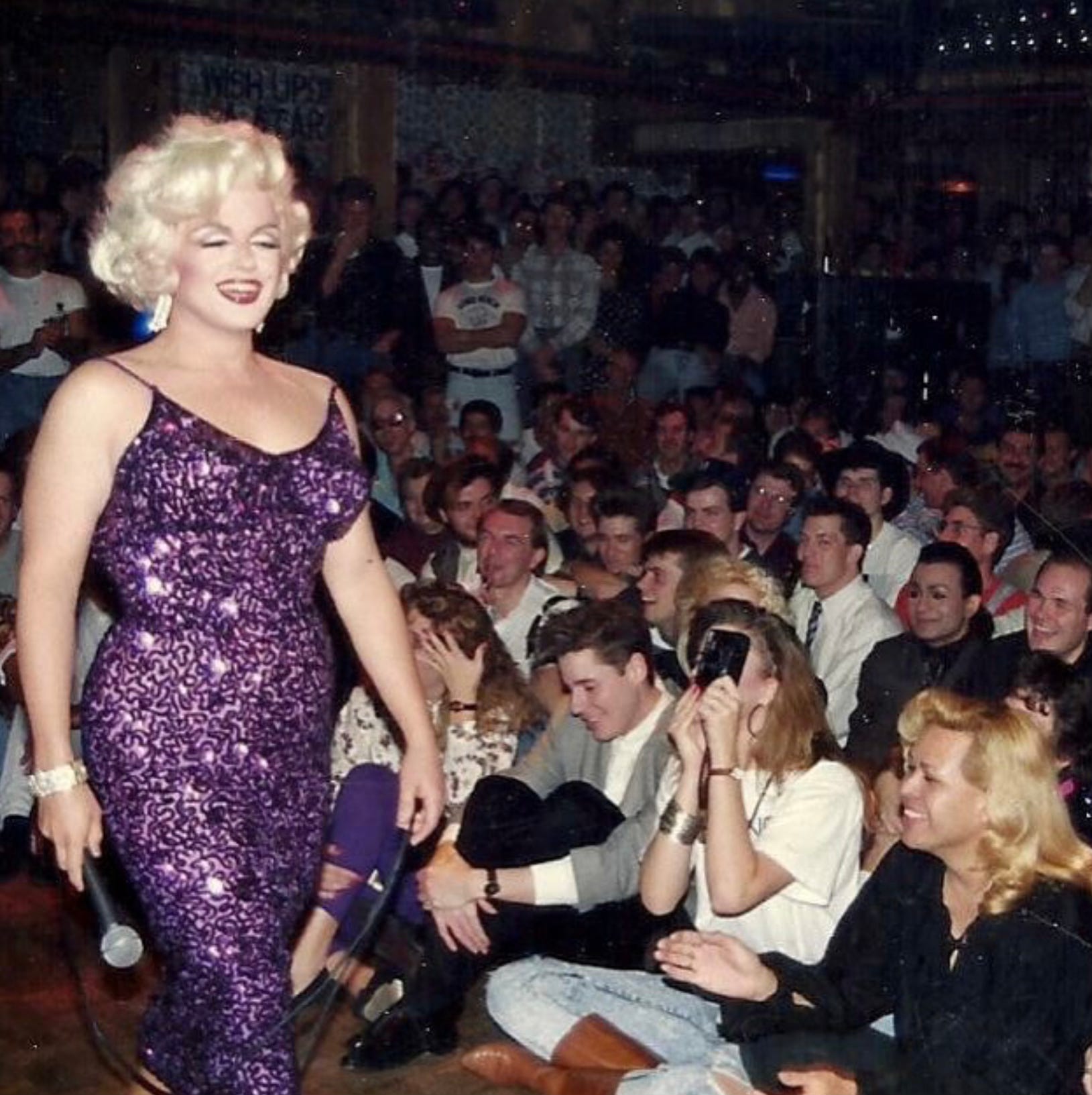

So, when I saw an ad announcing that Jimmy James — famous for his spot-on impersonation of Marilyn as documented on Donahue — would be appearing at one of my favorite gay clubs, Vortex on N. Halsted, on January 19, 1991, there was no question I would be there.

I only made $45 a week working as an assistant at a literary agency before graduation, but I had enough to take the Jeffery 6 bus from my Hyde Park campus, get off in Boystown, pay the cover charge and stake out a spot in the packed-like-sardines crowd waiting to see if Jimmy James lived up to the hype.

“Isn’t it amazing how they get those big fish into those little glass jars?” — Marilyn Monroe, “Some Like It Hot” (1959)

Jimmy’s show was more like a magic act than a drag show. When he emerged as Marilyn, shimmering in a tight spotlight, he hypnotized us with the suggestion that this was Marilyn Monroe in the flesh. I wasn’t in the front row, but everyone in the relatively small house had a close-up view, allowing us to drink in his artistry, his second-nature mannerisms, his shockingly authentic hair and makeup and a dress that looked like Jimmy started laying plans for it when he was about 13.

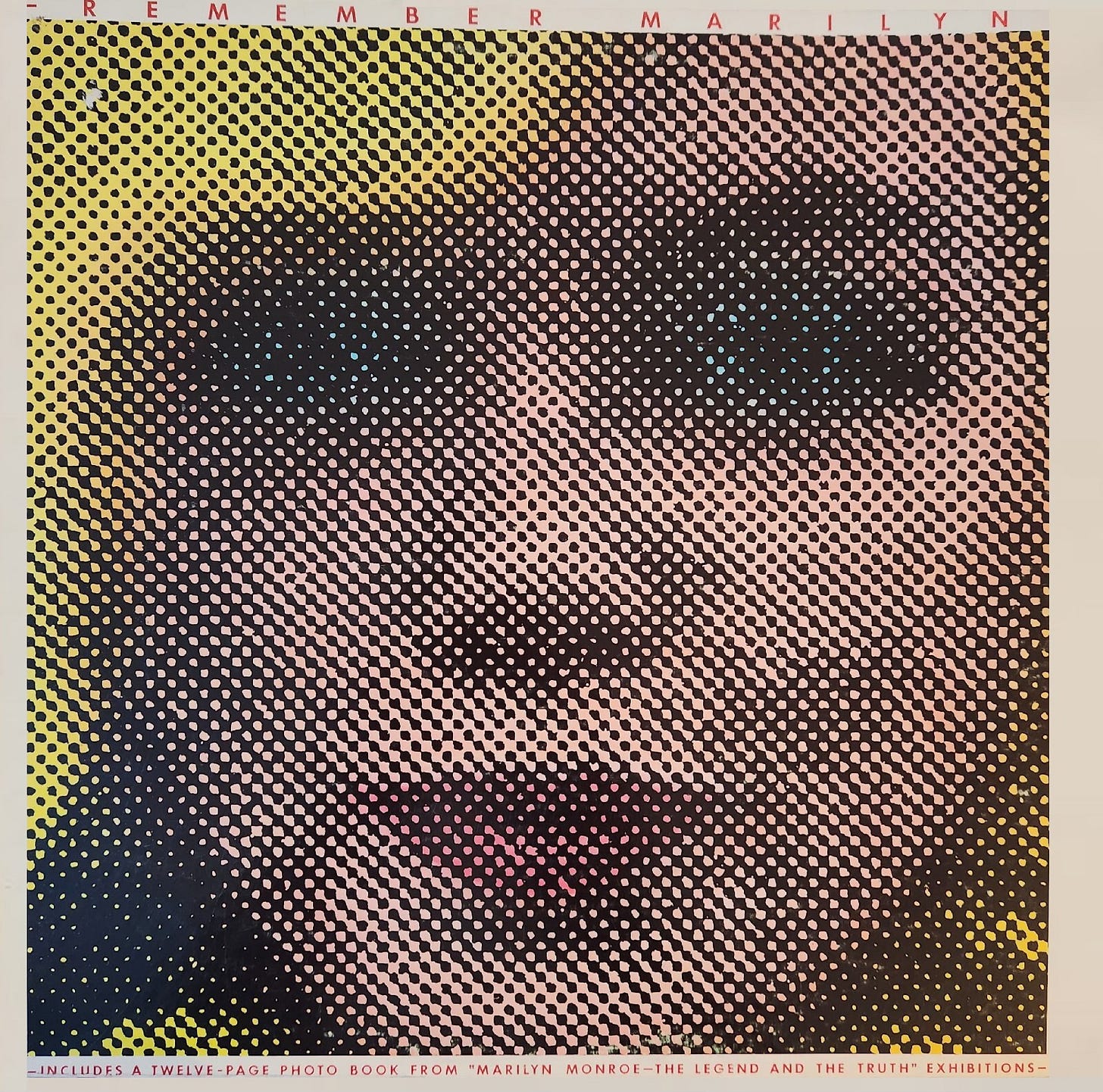

Most thrilling was the voice. “Hi, honey!” he would coo, sounding exactly like Marilyn in any of her movies or on the album I’d bought at Hyde Park Records and committed to memory, Remember Marilyn. I wasn’t old enough to remember Marilyn, but at least I would always remember Jimmy James.

“It shakes me, it quakes me, it makes me feel goose-pimply all over.” — Marilyn Monroe, “The Seven Year Itch” (1955)

It could have been chilling — like seeing a ghost — but Jimmy wasn’t playing dead Marilyn, he was playing live Marilyn. It was a friendly reincarnation, not a seance. And as perfect and retro as his performances of her songs were, his stage banter had 1991 touches, giving a glimpse into what Marilyn may have been like as a cabaret act 30 years after her death.

It has now been longer since I saw Jimmy James for the first time than it had been between Marilyn’s death and Jimmy’s show at the Vortex.

In the intervening years, James made many more TV appearances before retiring his visual tribute to Marilyn in 1997. He has continued working in clubs, where he offers drop-dead perfect impressions of everyone from Cher to Bette Davis, and where he also sings as none other than Jimmy James, including his dance hit “Fashionista.” He gave a series of well-received COVID-era Facebook Live performances from his San Antonio, Texas, home accompanied by his beloved mother, since departed.

He is no longer Marilyn, but he is eternally gifted with a mic, has never lost his flair for making a small space into a big production and is as funny and over-the-top as ever.

Now, as he continues to digitize his extensive archive in anticipation of production of a proper documentary — The Boy Who Was Marilyn, collaborating with Blake Devillier — I spoke with the the one and many … Jimmy James.

I want to start out by asking you to explain a little bit about what you’re doing with your archive right now.

JIMMY: Oh, my God! This guy [Blake Devillier] stepped in at the right time. Mom passed away almost two years ago and left me with a mess … Mom was a bookkeeper and was so organized with bills and everything. I would just give her the money. She’d take care of the bills. I hardly even knew how to write a check! But it was a slow decline into dementia.

You were so close to your mom. I know it was a hardship caring for her, but did you wind up feeling blessed to have been near her in her final years?

JIMMY: Oh, yes, and the pandemic was, ironically, a gift. I had lost all my gigs that year. My mom chose Jude as my middle name, so she had some affinity for St. Jude — the Patron Saint of Lost Causes. [Laughs] Whenever I’m in a tight situation, I have this picture of St. Jude framed right outside my bedroom. When everything shut down and I lost all my gigs, I didn’t even pray — I looked at the picture of St. Jude. I said, “Let’s see how you get me out of this one.” The joke was on me. I got tons of money from tips doing living room concerts on Facebook every Thursday, I got two PPP loans, I got unemployment from California. I was rich.

I got to spend that time with Mom, and she would do the Hail Mary because she was very devoted to the Blessed Mother. I think everybody needed that moment of prayer. People kept requesting, “Is she going to do the Hail Mary?” It changed the molecular energy in the room. I had to hold back from crying because it was so powerful. My mom wasn’t in show business, but she had that little ministry of hers. There was no vaccine, Orangina was in office the first time — we were just in free fall.

Was she always supportive of you, even in your childhood?

JIMMY: Yes, always. But there was a point when she found out I was doing, quote, unquote, drag, early ‘80s. She blew the lid off. She didn’t understand. You have to understand my mom comes from a very Catholic family, and her brother was a priest. Her sister is a nun. Mom was the oldest kid of 12. I was the first-born, the oldest of four kids. We had a kindred spirit. Not that she didn’t get along with my other siblings; she did. But I can tell you Mom had a good time in the living room concerts because I was gone for so many years. Thirty-five years, I basically lived in New York or L.A. and back and forth and traveled. I’d come to San Antonio to decompress, but I normally didn’t perform in San Antonio. If I ever did, she would go see me.

But the pandemic shows she looked forward to because she was falling into a depression. My mom would go to church every day from 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. When the pandemic happened, of course, nobody could go to church. I had to think of something. It broke my heart. I came up with the idea of doing living room concerts. My friend that’s good at social media said I should charge $5. I said, “No, I’m not going to charge.” He says, “Well, you need money, too.” I didn’t want to charge because people were hurting. And honestly, it was like the Barbie song — I found what I was made for.

It’s incredible that you found such a creative calling at a time when so many people were giving up.

JIMMY: I truly did. And I compromised and added a tip jar. Honey, the fans, it’s a funny thing. I really learned this from Amanda Palmer’s “The Art of Asking” TED Talk about when she used to do those statues, but they have to be real still and people come around and take pictures with them. They would take their picture and they’d give her a tip, and she’d bend over and give them a little flower. She said, “That was the magic between them wanting to give to me and me wanting to give to them.” You just give. Don’t expect anything. It’s funny how it comes back. I thought I’d make $100, maybe $200. Oh, no. I made $500, $600, $800, $900.

Every Thursday was a different show. I’m cut out for that because I, for many years, did Pieces in New York on a Monday night, and it was always a work in progress. For five years, it was Monday nights, and I came up with different songs. I was experienced in doing that, and it was great.

It was magical. The stars aligned to give me this time with Mom. I always thought, “God, I don’t spend enough time with Mom. The years are going by now. She’s elderly.” It was a miracle.

Something so positive out of a negative situation!

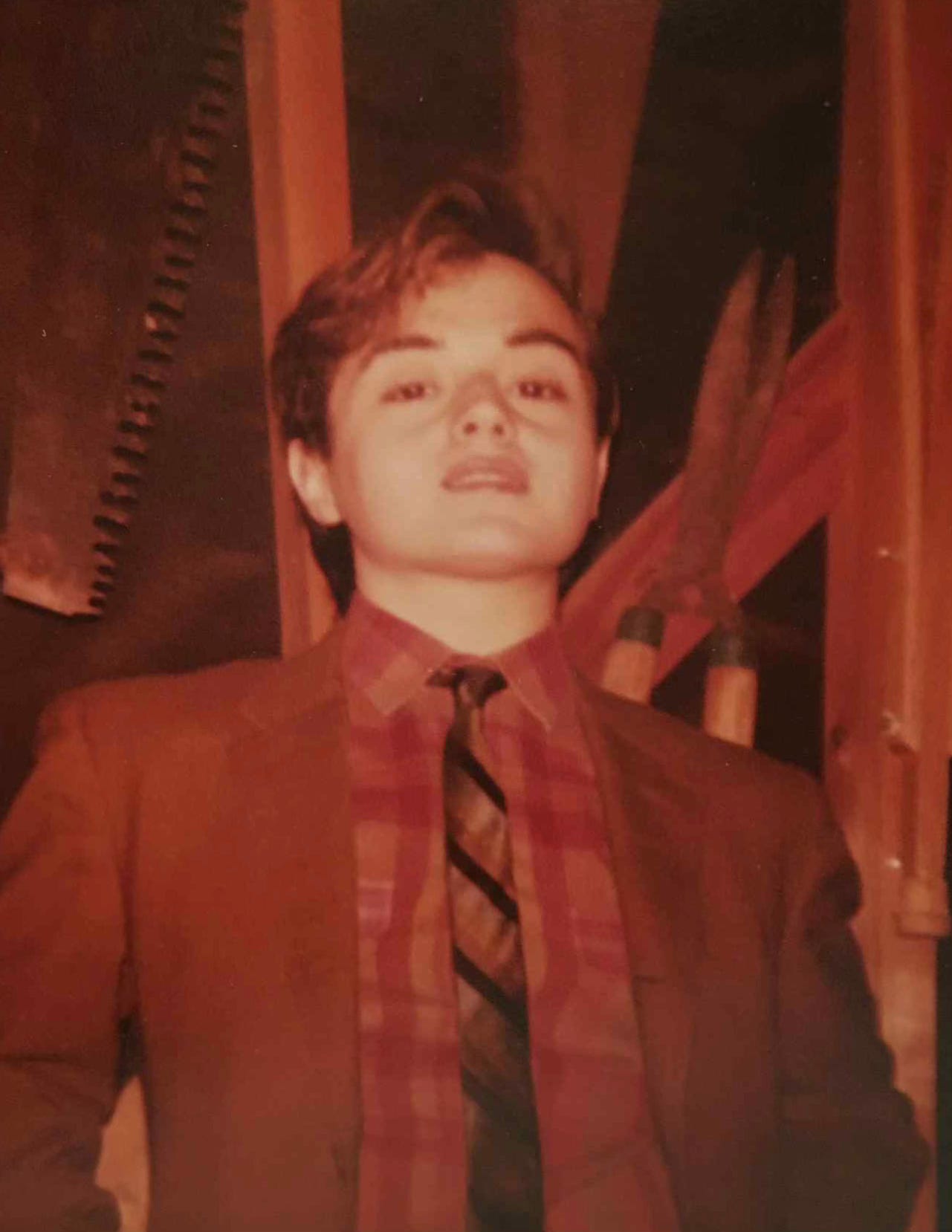

JIMMY: I think people turned to our little show for comfort, and I used it to do what I was made to do. At 11 years old, I had a premonition, a voice that spoke to me. I thought I was going to be a teacher. I was playing on the chalkboard in my garage. It was a double-wide garage and I lived in suburbia. I’m on the chalkboard, pretending like I’m a teacher in an imaginary class. Then something stopped me. It was like an awareness. Something said, “You’re not going to be a teacher.” I was like, “I’m not?" What am I going to be?” This is all just in my head. It wasn’t verbal. It said, “You’re going to entertain people.”

Then, the next question: “Am I going to be rich?” I didn’t like what the voice said. It said, “Wellll, no, but you’re going to be okay.” [Laughs] I can tell you I’m not a rich white woman like RuPaul.

I said, I’m going to remember this moment, because it was so profound and it was something that spoke to me in Bumfuck, San Antonio. San Antonio has grown exponentially since then, but back then, it was podunk. Why would this voice be telling me that ? I would be an entertainer? I had no money to board a flight and go to New York or Los Angeles or any of that. I had no idea.

What were you like pre-Marilyn?

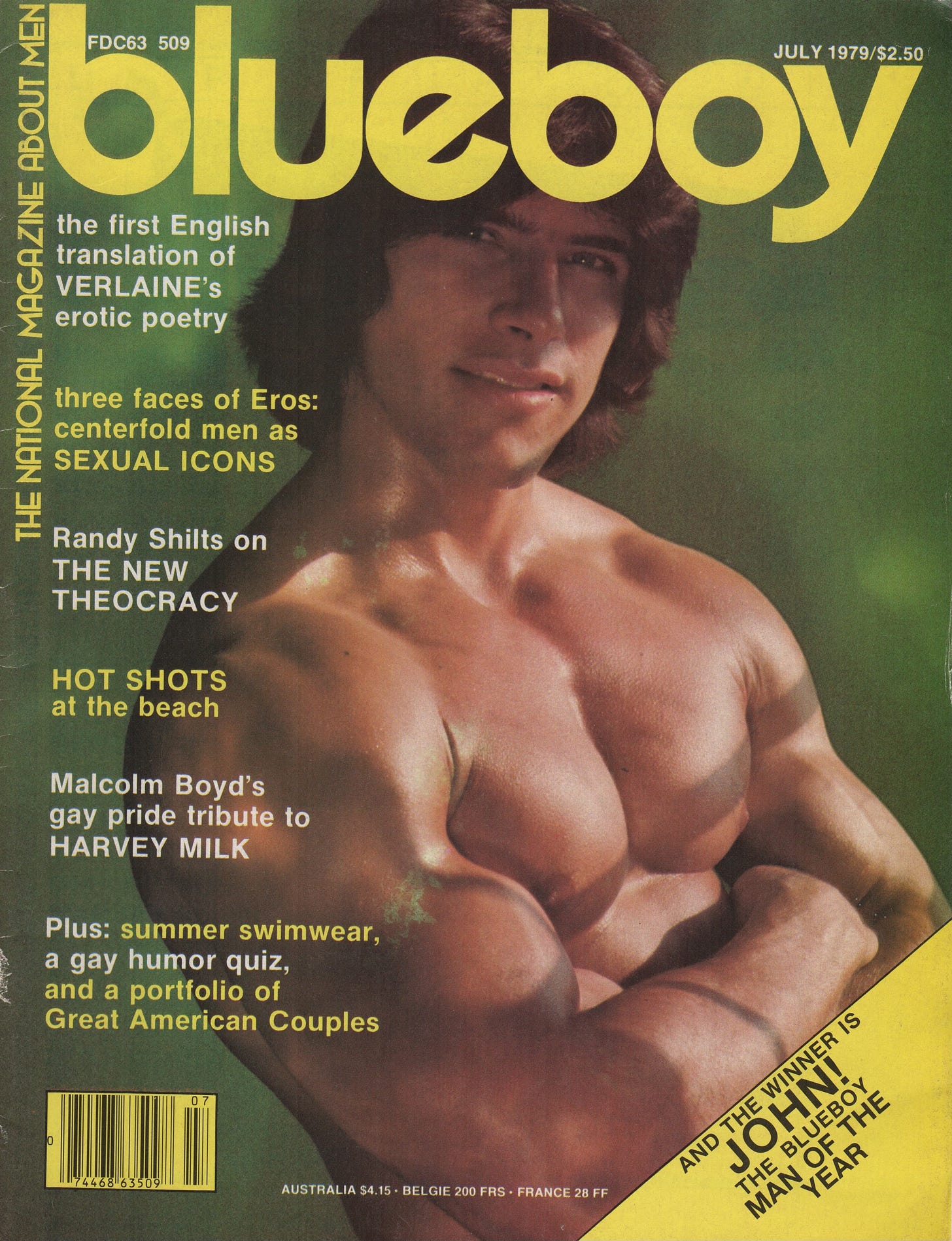

JIMMY: I was suicidal at 20. I had the face of a girl, the voice of a girl. On top of it, I was a chubby kid who didn’t fit in anywhere. Do you remember Blueboy magazine?

Are you kidding me?

JIMMY: So this is how they ruined me. Of course, they had hot boys in there, right? That was fine. But in the personal ads in the back, “I’m looking for this, looking for that, no fats, no femmes.” Every one said “no fats, no femmes.”

So I thought, “I’m the most reviled in the gay world.” Now, at that point, I didn’t have Marilyn. I lost weight, but in my head, I was still a fat boy. Even if I’m slim, I knew I was still going to be considered a femme, so nobody would want me. “The gays don’t even want me!” I mean, that was just in my head.

How did you pull out of being suicidal?

JIMMY: There’s a couple of issues. One, I couldn’t do that to my mom, but I thought of suicide constantly, every day. That’s why I wanted to do a documentary. I want to help people who find themselves in a very dark place, and tell them you have to give yourself a chance. Number two, Catholics consider that a mortal sin. Because only God decides when you leave the planet.

Joan Rivers said — I wish I could find what show that was — she said something to the effect of, “You have to give yourself a chance. It’s going to turn around.” Do you know that was so valuable to me"? Years later, I was on her show.